Looking Through the Cyclical Slowdown in China’s Consumption

Looking Through the Cyclical Slowdown in China’s Consumption(Yicai Global) Jan. 16 -- When the National Bureau of Statistics releases its National Accounts for the fourth quarter of 2022, the data will likely show a sharp slowing in consumption. The recent Urban Depositor Report, published by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), can help us understand why Chinese shoppers kept such a tight hold on their purse strings.

The PBOC has been surveying depositors since 1999. It randomly selects fifty depositors from each of 400 bank outlets in 50 large, medium and small cities to construct a broad-based sample of 20,000 respondents. It then transforms the answers to its questions into “diffusion indices” where a reading of 50 acts as the dividing line between expansion and contraction.

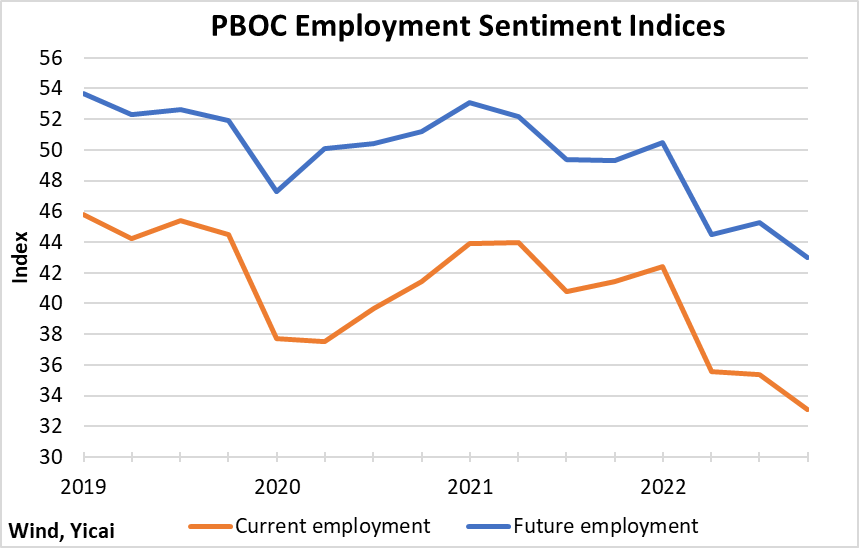

According to the depositors surveyed, the labour market became more precarious during the fourth quarter. Fewer respondents felt it was easy to find a job. In addition, a smaller share felt that prospects for job hunting would improve. The PBOC’s indices for “current” and “future” employment sentiment fell below their 2020 troughs in the second quarter of last year and subsequently have declined further with new lows being reached in Q4 (Figure 1).

Figure 1

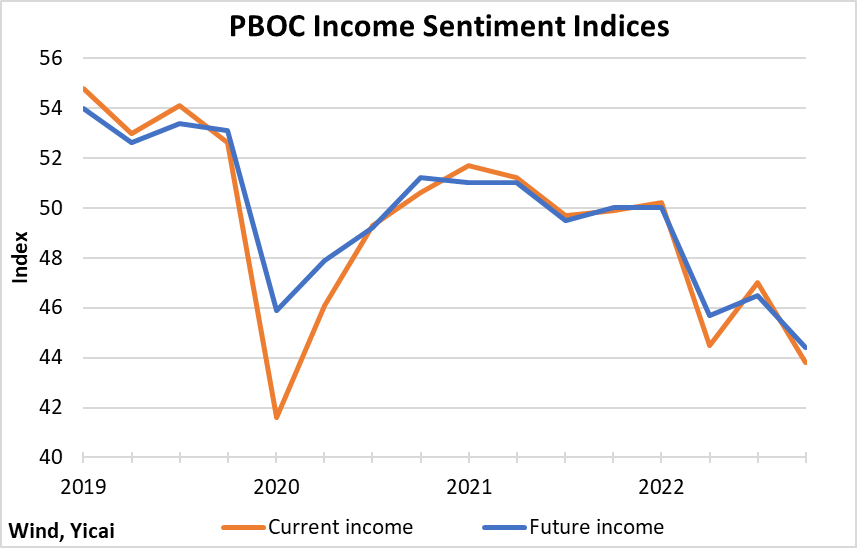

Given the labour market weakness, fewer depositors said that their incomes were currently rising. Moreover, they were increasingly pessimistic about their prospects for higher incomes in the future. However, the deterioration in income sentiment was less pronounced than that of employment. For example, the current income sentiment index remained above the 2020Q1 trough throughout 2022 (Figure 2). This suggests that workers were less likely to change their existing jobs for those that paid more, presumably because there are fewer such opportunities now.

Figure 2

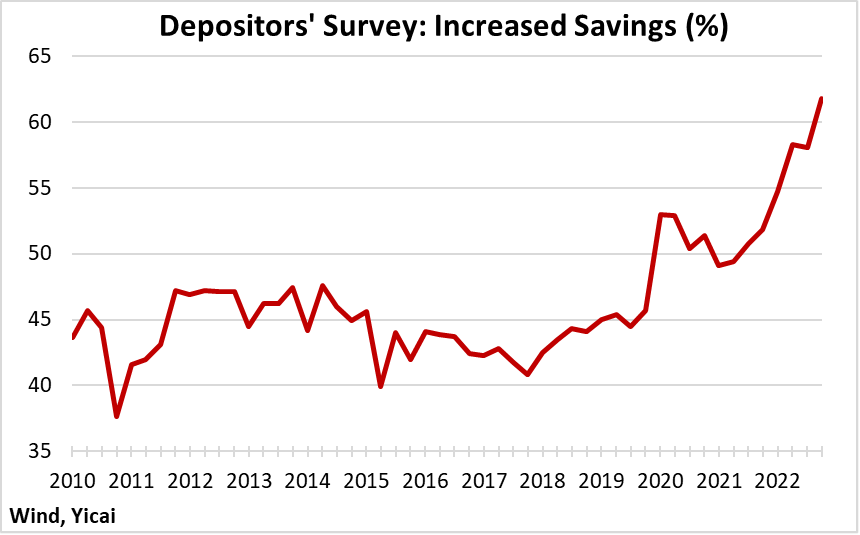

The PBOC also asks depositors whether they expect to spend, invest or save more. With the Covid outbreak, depositors’ desire to save jumped and it has continued to rise (Figure 3). In 2022Q4, close to 62 percent said that they would increase their savings – the highest share the PBOC has recorded.

Figure 3

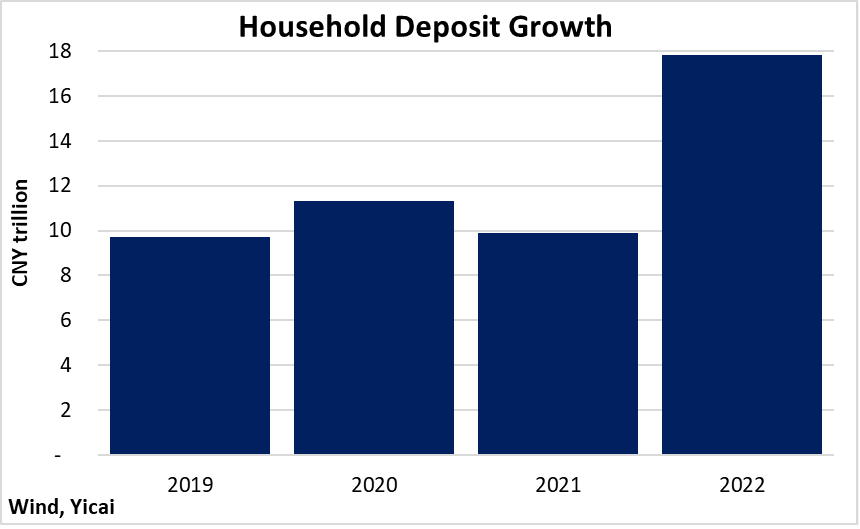

And households have indeed saved. Their deposits in the Chinese banking system rose by nearly CNY18 trillion last year. Between 2019 and 2021 household deposits rose, on average, by CNY10 trillion (Figure 4).

Figure 4

I want to address a common perception that the Chinese economy has long suffered from insufficient consumption.

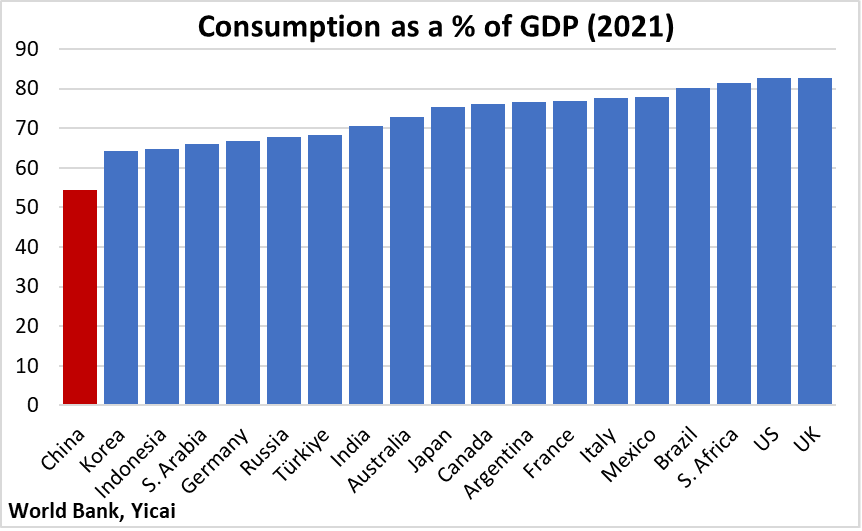

It is true that consumption has typically accounted for a much smaller share of GDP in China than in other major economies. Figure 5 shows the consumption shares for 2021 (the World Bank data used here defines consumption to include current spending by both households and governments). China’s share was 54 percent of GDP which was well below the G20 average of 73 percent.

Figure 5

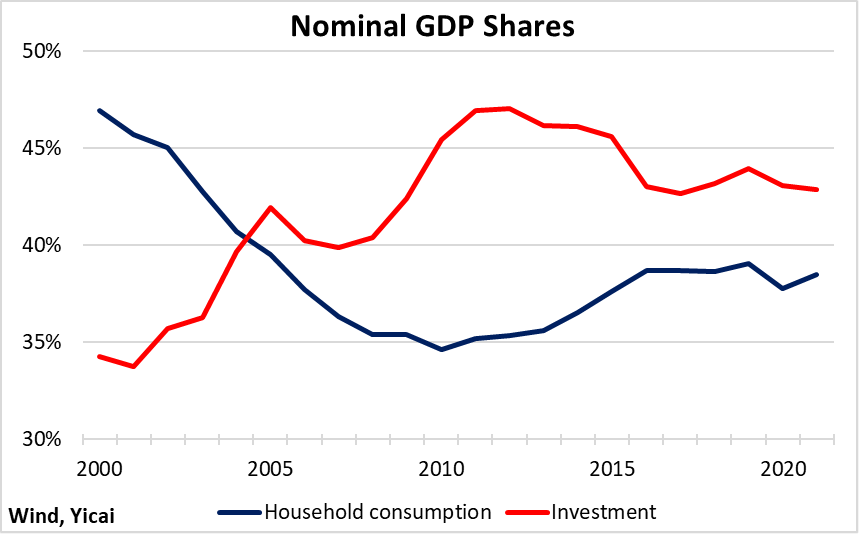

The low share of consumption in China’s GDP is an artifact of its very rapid economic development. In particular, in the first decade of the 21st century, China invested heavily to create the modern capital stock needed to raise the living standards of its people (Figure 6). While consumption grew rapidly –between 2000 and 2010 it rose by 10 percent, in real terms, annually – investment rose even faster.

Figure 6

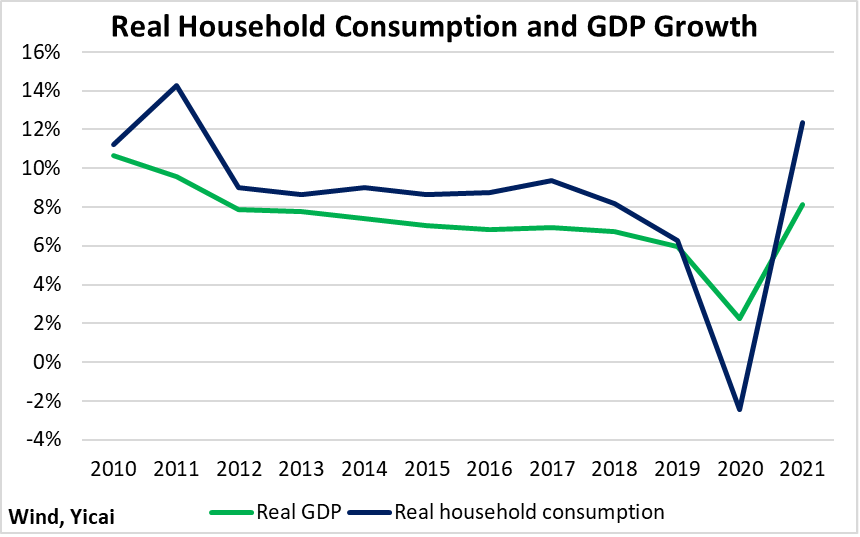

By the early 2010s, the situation began to reverse. With more of the capital stock in place, the investment rate began to decline and the share of household consumption in GDP began to rise. Over the last decade, China’s household consumption has grown faster than its GDP (Figure 7).

Figure 7

I believe that the fall in consumption last year and the associated increase in savings is a cyclical phenomenon brought on by Covid and its impact both here in China and abroad.

With the build-up in households’ savings, consumers certainly have enough “dry powder” to set off a consumption boom. The CNY8 trillion in “excess” household deposits is close to 7 percent of GDP. The question is when will the pent-up demand be released?

The 2023 McKinsey China Consumer Report concludes that China’s increasingly affluent consumers are proving to be resilient. It predicts that if and when consumers bounce back, they will certainly have a lot of money to spend. I commend this excellent report to you.

McKinsey’s analysis draws on a nationwide survey of 6700 Chinese consumers conducted in July 2022. Their responses suggest that the downturn in consumption is cyclic.

Fifty-four percent of those surveyed believed that their incomes will increase significantly over the next five years. This was only a slight drop from their 2019 survey when 59 percent expressed that view. Moreover, the respondents in McKinsey’s China survey were more optimistic than those in mature markets that their economy would rebound from the Covid-induced slowdown fairly rapidly. Respondents to the surveys McKinsey conducted in India and Indonesia were even more optimistic than those in China.

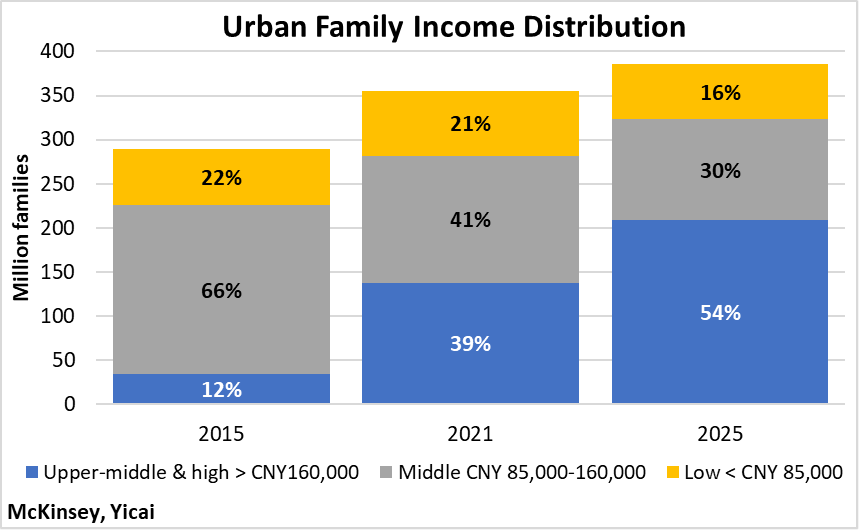

McKinsey believes that consumption will be supported by the rapid growth in more affluent Chinese households. Those in the upper-middle and high-income group accounted for 55 percent of urban household consumption in 2021 even though they only made up 39 percent of all urban households. This group, which earns more than CNY160,000 (USD21,800) per year, is expected to make up 54 percent of all urban households by 2025 (Figure 8).

Figure 8

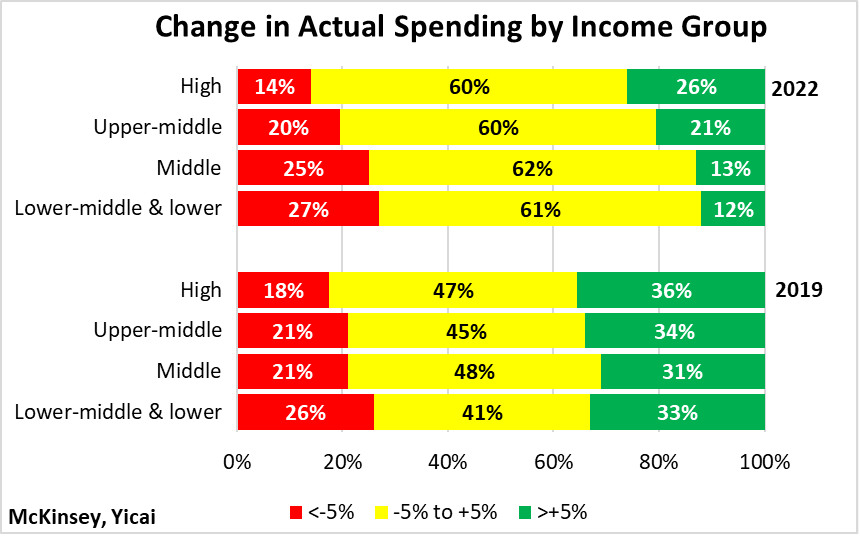

McKinsey’s surveys allow us to compare consumer attitudes toward spending last year with those before Covid hit and it illustrates the resilience of the more affluent group.

On average, across the four income groups, 18 percent of respondents said they would increase spending by more than five percent in 2022. This was down from 33 percent in 2019. Note that similar proportions in both surveys planned to reduce spending by more than five percent (Figure 9).

Twenty-six percent of the high-income respondents said that they still planned to increase spending by more than five percent in 2022. The decrease in willingness to spend compared to 2019 was the smallest among this group (from 36 to 26 percent), suggesting that the affluent group still had plenty of discretionary income to consume.

Figure 9

McKinsey says that consumers are finding ways to get more for their money. Some are buying through low-cost group or community ecommerce channels or they are choosing cheaper product lines within the same brand. Others are waiting for products to be discounted before making their purchases. And discounting is becoming a more prevalent marketing strategy.

McKinsey notes that domestic producers of consumer goods have increased the quality of their offerings, which now compete based on features and specifications rather than brand or country of origin. The ability of Chinese companies to move up the value chain and take market share away from foreign brands will help maintain domestic production and employment in a slower-growing market.

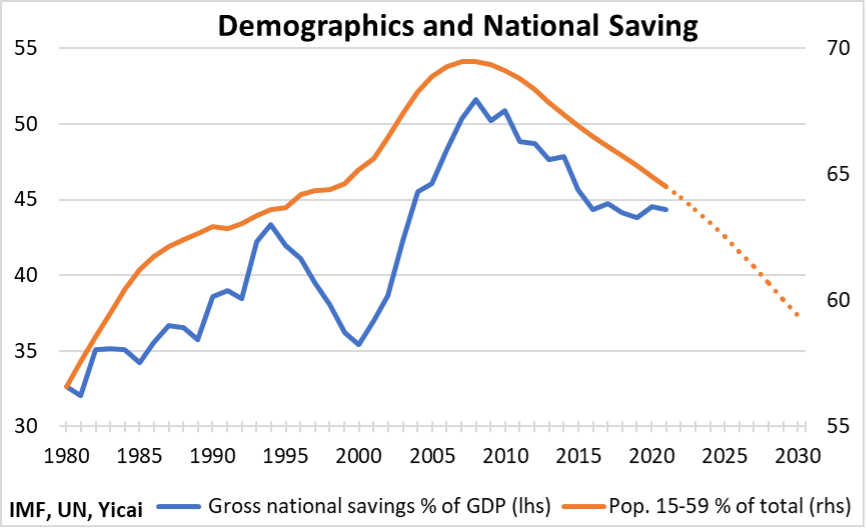

Another key factor that will underpin the growth of consumption is demographics.

In the three decades since 1980, China’s national savings rose from one-third to more than one-half of GDP (Figure 10). During this period, the working-age population was on the rise. Those in their working years are not only the earners, they are also the savers. As the population ages and retires, it begins to draw on its savings to fund its purchases.

Figure 10

China’s working-age population has already peaked as a proportion of the total population. Demographic projections suggest that China’s savings rate should continue to fall through the end of the decade.

A falling savings rate does not, by itself, ensure rapid consumption.

Income growth must be maintained as well, either through high-quality investment in physical and human capital or through improvements in total factor productivity. Thus, policymakers need to look through the cyclical slowdown of consumption and continue to focus on improving the economy’s long-term prospects.