Analyzing Happiness Under Lockdown

Analyzing Happiness Under Lockdown(Yicai Global) April 1 -- The lockdown in Shanghai has intensified. The city has moved from a “district-by-district, neighbourhood-by-neighbourhood and building-by-building” to a stay-at-home order covering all of eastern Pudong and areas in western Puxi.

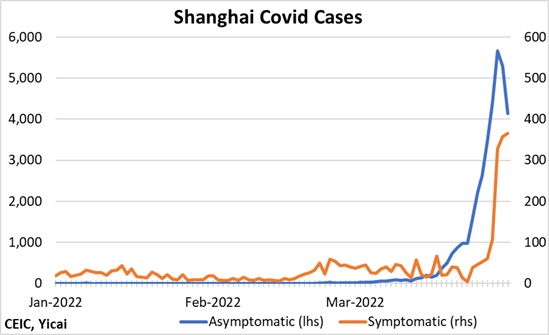

The change of strategy is, no doubt, due to the explosion of cases in the last week. Shanghai’s total cases – symptomatic and asymptomatic – increased from 1624 on March 24 to 4510 on March 31. Ninety-two percent of the cases are asymptomatic (Figure 1).

Figure 1

New infections in Shanghai (symptomatic and asymptomatic) are about 20 per 100,000 residents. This is somewhere between the current infection rate in the US (9) and the EU (100) but well below the peaks recorded by those two economies in January (240 and 280, respectively). In locking the city down, the authorities are being forward-looking and hoping to control the virus’s spread before it gets out of hand. Hong Kong’s recent experience likely weighs heavily on their policy choice.

The restrictions we face at home have tightened as well. We are no longer free to roam around our compounds but must remain in our apartments. We can only go outside to throw out our garbage and to take our Covid tests.

Sitting at our kitchen table, my wife scours the internet to find vendors who are able to deliver food. When she finds someone, she shares their coordinates with the hundred-odd members of our building’s WeChat group. Our neighbours have been great about sharing information and food too, if more has been delivered than they can use.

Our family is lucky. My wife and I are able to work from home even though our productivity suffers from our daughters’ not being in school. Still, we have no ongoing medical issues that require external care. And, our 90 square-meter apartment is big enough for the four of us.

We try to keep an even keel by maintaining our routines. Our older daughter diligently takes her Grade 4 classes online. My wife helps our five-year-old practice piano and guides her with crafts, all the while completing her office tasks on her cell phone. Alone in the bedroom, I immerse myself in interesting datasets.

I was fortunate to be able to occupy myself with the recently World Happiness Report (WHR) and it seems that time just flew by as I crunched through its numbers. At the core of the WHR is a survey done by the polling company. The Gallup World Poll asks respondents to evaluate their current life as a whole using the mental image of a ladder, with the best possible outcome on the 10th rung and the worst possible on rung zero.

Gallup has been polling people around the world on their happiness since 2006. Beginning in 2012, a group of economists, spearheaded by Columbia’s Jeffery D. Sachs, published the first WHR and a new edition is released each year around March 20 (International Happiness Day). The Reports review the evidence from the emerging “science of happiness” as part of an effort to go beyond GDP in measuring economic and social development.

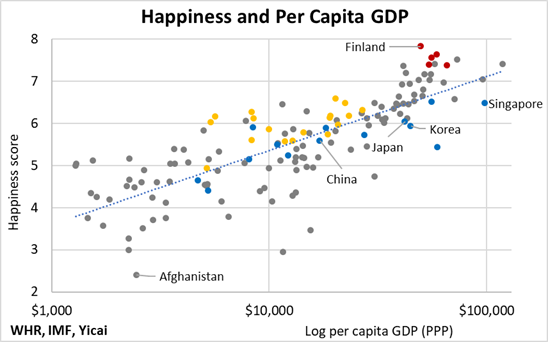

In the 2022 edition of the WHR, the country-by-country data were released as averages of the results for 2019-21 (Figure 2). Across the 143 countries surveyed, happiness was the highest in Finland (7.8) and the lowest in Afghanistan (2.4).

Figure 2

There is clearly a strong positive relationship between per capita GDP and happiness. However, this relationship is not linear (note that we are plotting the log of per capita GDP on Figure 2’s horizontal axis). Countries experience smaller and smaller gains in happiness for every USD1000 increase in per capita GDP. Indeed, the cross-country data imply that incomes need to double for each additional 0.5 increase in the happiness score.

While income is obviously important, there also seems to be a cultural aspect to happiness.

Latin American countries fall into the middle-income range and they are, in general, happier than one would expect. I have coloured them yellow in Figure 2 and most of them lie above the trend line, which represents the typical happiness level for a given amount of per capita GDP.

Given the popularity of happiness research, the out-performance of Latin American countries is well documented. notes that despite socio-political indicators showing Latin American countries suffer from weak political institutions, pervasive corruption, elevated crime, a very unequal distribution of income, and high poverty rates, their happiness situation is very favourable. He attributes this to the abundance of “family warmth” and other supportive social relationships. The Latin American culture, he explains, has a human-relations orientation and a relative disregard for material values, which leads people to be happier than their per capita GDPs would predict.

In contrast, East Asian countries, coloured blue in Figure 2, appear to be less happy than one would expect given their incomes. China, Korea, Japan and Singapore all lie below the trend line. Cross-cultural research on happiness that family expectations have a substantial impact on people in East Asian cultures. This could manifest as the sacrifice of one’s own happiness for that of other family members or pressures to conform to parents’ wishes.

The third group that stands out in Figure 2 is the Nordic countries (Finland, Denmark, Iceland Norway and Sweden), which I have coloured red. These countries are perennially among the highest scorers in the annual WHRs. Indeed, Finland has been ranked as the happiest country in the world in each of the last five years.

Researchers are hard at work trying to find the Nordic countries’ secret recipe for happiness. Savolainen that Nordic countries have an ethos of humility. While the accumulation of material wealth is seen as a symbol of success in many countries, the Nordics prefer to keep a low profile. The best-known formulation of this ethos is , which comes from the 1933 novel “A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks” by Danish-Norwegian author Axel Sandemose. This ethos imposes a penalty on the boastful and puts a premium on a life that “”.

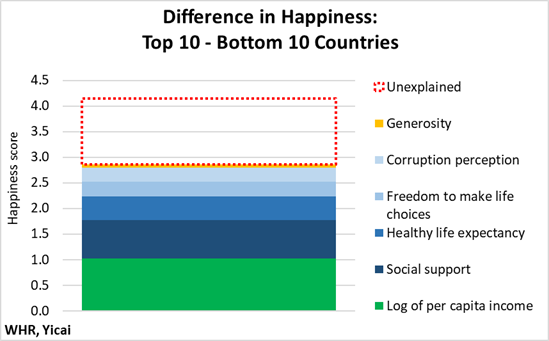

Rather than rely on cultural explanations, the WHR’s authors use econometric techniques to analyze why some countries are happier than others. Their model includes five variables in addition to the log of happiness: healthy life expectancy, social support, freedom to make life choices, generosity and corruption perception.

Figure 3 shows how the authors apply their model to explain the difference in happiness between the top 10 countries (which had an average score of 7.5) and the bottom 10 countries (whose average score was 3.3). The higher incomes in the happiest countries explain about a quarter of the four-point happiness difference. Together, the other five variables explain an additional 44 percent. This suggests that non-economic factors can play a significant role in increasing happiness. About a third of the difference between the most- and least-happy countries remains unexplained, so there is still plenty of scope for research into happiness’s determinants.

Figure 3

The Gallup scores for China show a rise in happiness over time from 4.7, on average, in 2006-09 to 5.5, on average, in 2019-21 (Figure 4).

China’s 0.8 point increase in happiness can be fully explained by the rise in per capita GDP (PPP basis), which was up 2.5 times between the two three-year periods. China’s experience indicates that a further doubling of per capita GDP will increase its happiness by 0.6 points (this is slightly more than what the cross-country data suggest). At 5 percent growth, its per capita income would double in 2036. In the meantime, there is a potential role for non-economic factors in making Chinese people happier.

Figure 4

Pudong’s lockdown was to end on April 1. However, the most recent communication from Shanghai’s officials indicates that it will be extended. Our freedom of movement will be dictated by the existence of infections in our building, our neighbourhood and our district. Nevertheless, we are thankful for our good fortune and hopeful that our normal lives will resume soon.