How Should We Think About State-Owned Enterprises’ Low Profitability?

How Should We Think About State-Owned Enterprises’ Low Profitability?(Yicai Global) July 8 -- Are state-owned enterprises (SOEs) a millstone around the neck of the Chinese economy?

For decades, SOEs have been less profitable than their private sector counterparts. In 2021, the assets of industrial SOEs amounted to CNY 52 trillion. These assets generated profits of CNY 2.3 trillion for a return on assets (ROA) of 4.4 percent. In comparison, private firms had industrial assets of CNY 90 trillion. And they were able to earn an ROA of 7.2 percent.

Had the SOEs been able to achieve a 7.2 percent rate of return on their assets, their profits would have been CNY 3.7 trillion. The difference between what they actually earned and what they could have earned is CNY 1.4 trillion, or 1.3 percent of GDP. With economic growth in the 5 to 6 percent range, the SOEs’ under-achievement seems to be quite significant.

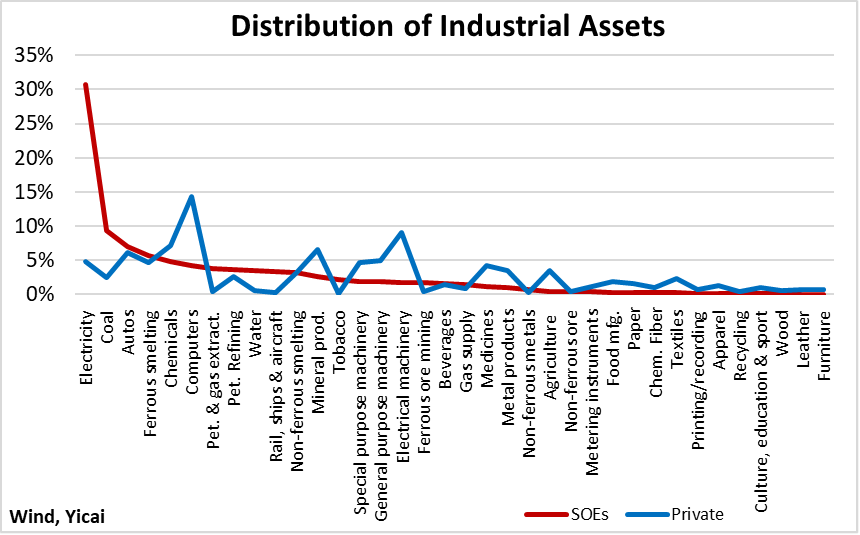

One reason that the SOEs are less profitable than private firms is that they are engaged in more asset-heavy businesses. Figure 1 shows just how differently the industrial assets of SOEs and private firms are distributed. Most of the SOEs’ assets are invested in utilities. Thirty-one percent are devoted to the production and supply of electricity. Given the scale of the electrical grid and the plants that generate the country’s power, this is, indeed, an asset-heavy undertaking. An additional 5 percent of the SOEs’ assets are devoted to supplying water and natural gas, which also require the construction and maintenance of vast networks. The private sector only has 6 percent of its assets in the utility sector.

Figure 1

Another very asset-intensive sector is the extraction of fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas. Nine percent of the SOEs’ assets are invested in coal mining, the second most important sector after electricity generation and distribution. A further 4 percent is invested in the extraction of oil and natural gas. The private sector only has 3 percent of its assets invested in fossil fuel extraction, compared to the SOEs’ 13 percent.

While close to half of the SOEs’ assets are invested in utilities and fossil fuel extraction, state-owned firms do engage in manufacturing. Automobile manufacture accounts for 7 percent of SOE assets, 6 percent are invested in the smelting and manufacture of ferrous metals and 5 percent are in the manufacture of chemicals. These are all quite asset-heavy sectors.

The private sector’s assets are distributed more evenly across the range of industries. The largest share of their assets, 14 percent, is invested in computers and communication equipment. Nine percent is in the manufacture of electrical machinery and equipment and a further 7 percent is invested in non-metallic mineral manufacturing. These three sectors rank in the middle of the asset-intensity spectrum.

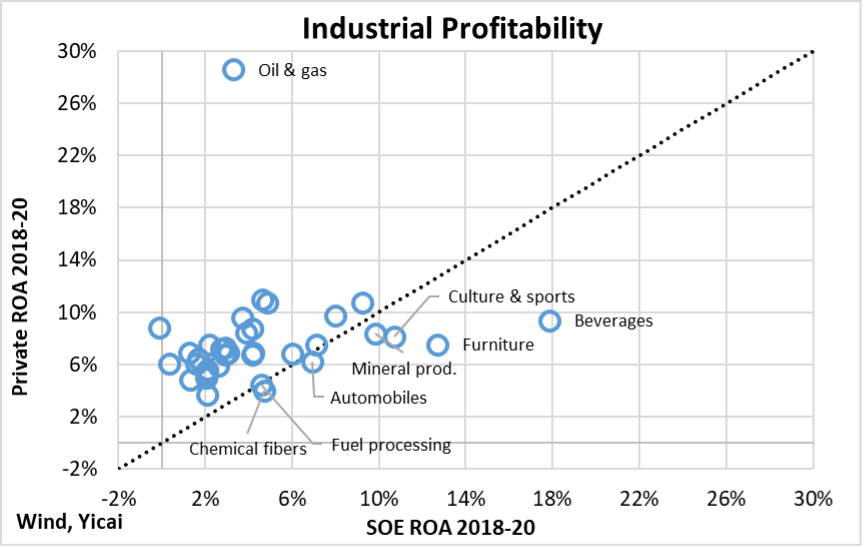

With SOEs and private firms, to a large extent, operating in different sectors, we need to take a more nuanced approach to comparing their profitability. Figure 2 presents the ROA across 36 industrial sectors with those of the SOEs and the private firms shown along the horizontal and vertical axes respectively. The data used are the averages for the three-year period 2018-20.

Figure 2

The dotted 45-degree line divides the group into those sectors in which SOEs are more profitable (below the line) and those in which the private sector is more profitable (above the line). Twenty-nine of the 36 industries lie above the line. This analysis shows that once we correct for asset-intensity, by looking on a sector-by-sector basis, that private firms are still more profitable.

There are some anomalies. SOEs are more profitable in the furniture sector. However, SOEs only account for 1 percent of the assets in this sector, which suggests that there may only be one or two very good state-owned firms in the largely private furniture industry. A similar story could be told for the culture and sporting goods sector in which SOE assets only account for 3 percent of the total.

On the other side, private firms seem to be much more profitable than SOEs in oil and gas extraction. However, with SOE assets accounting for 88 percent of those in the sector, there may only be a couple of very strong private firms.

Would China be better off by simply privatizing the SOEs and allowing more efficient private firms to take over?

Not necessarily.

According to , even though SOEs might be less profitable than private enterprises, there are at least three ways they can create economy-wide positive externalities that promote economic growth.

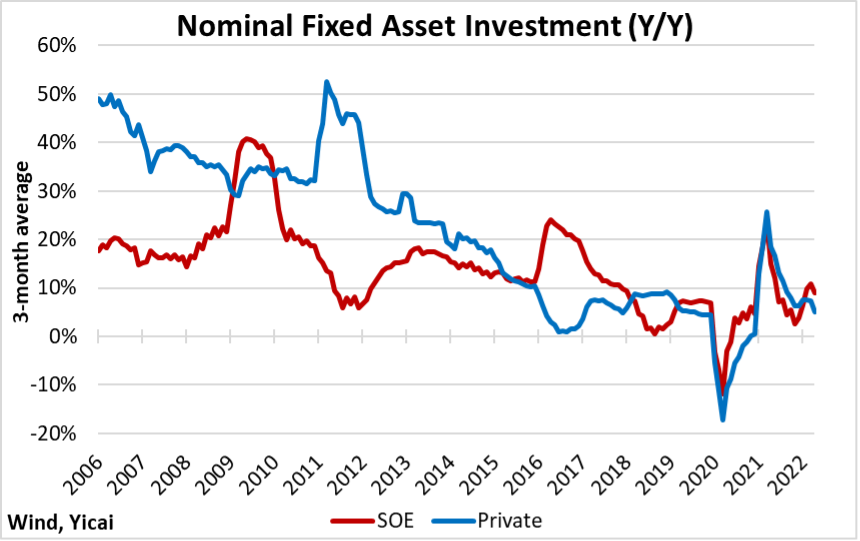

First, SOE investment has been used counter-cyclically to reduce the severities of economic downturns and prevent over-heating (Figure 3). In 2008-09 and 2015-16, investment by SOEs helped offset the weakness in spending by private firms. And state-owned firms are being relied upon again this year. Moreover, SOE investments can be slowed when private investment is buoyant as was the case in 2011 and 2018.

Figure 3

Second, Qi and Kotz show that SOEs have historically played a leading role in promoting technological progress. Currently, SOEs are being asked to invest in 5G, industrial internet, artificial intelligence, data centers and other new types of infrastructure.

Third, Qi and Kotz note that SOEs pay higher wages than private firms and typically require shorter working hours. Moreover, SOEs incur payroll costs to cover their workers for medical insurance and provide for pensions. Migrant workers hired by private firms often do not have these benefits. While SOEs’ labour practices increase their costs and reduce their profitability relative to private firms, they are helping to move China to a more consumption-based economy.

The good news is that the SOEs are closing the profitability gap.

Their ROA was 3.2 percentage points lower than that of private firms over 2018-20. The gap had been 5.3 percentage points over 2012-14. Moreover, it narrowed to 2.8 percentage points in 2021 and the data through May show that SOE profitability continues to catch up to that of private firms this year.

Some of the improvement in their profitability is due to selective downsizing. SOEs have been asked to exit areas which are not relevant to their core business or those in which their investments lack efficiency and competitiveness.

I remember taking a sun and sand vacation in Sanya at a hotel owned by a power-generating SOE from Shandong. I had a wonderful stay but it was surprising to me that the owner had invested in luxury, beach-side accommodation 2600 km away from its headquarters.

I propose three things to keep in mind when thinking through the SOEs’ low profitability.

First, SOEs’ core business and those of private firms can be different and difficult to compare.

Second, profitability is not the only factor that drives SOEs’ operations.

Third, the SOEs have improved their profitability over time as part of a larger program of .