What’s Driving China’s 15th Five-Year Plan?

What’s Driving China’s 15th Five-Year Plan?(Yicai) Nov 18 -- On October 23, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China adopted recommendations for formulating China’s 15th Five-Year Plan.

Governments at the national and local levels will use these recommendations in drawing up their own plans, which will include specific targets for the years 2026-2030.

The Central Committee’s recommendations are wide-ranging and cover many aspects of economic and social policy. I want to focus here on two key macroeconomic policies: the development of new quality productive forces and plans to increase household consumption. To my mind, both of these initiatives reflect policymakers’ efforts to mitigate the effects of China’s unfavourable demographics.

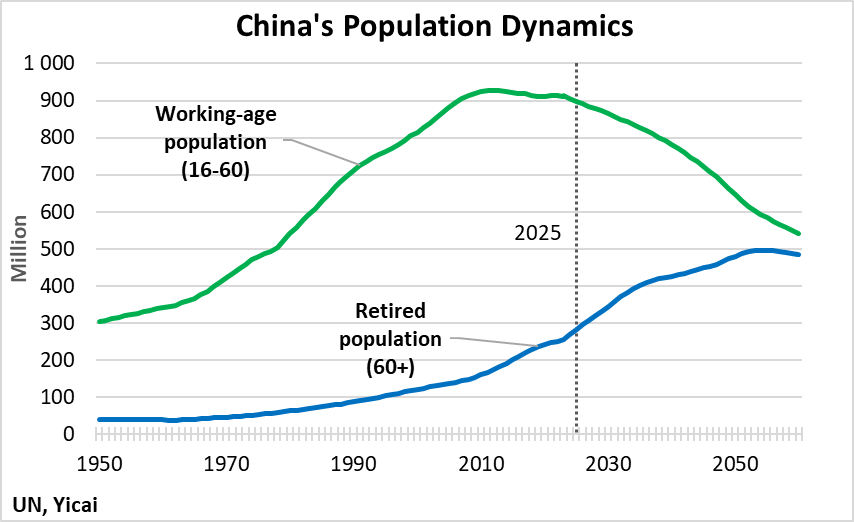

Demographic change in China is being driven by the declining number of working-age people and the increasing amount of retirees. These forces are already underway, but they will accelerate during the 2026-30 period and in following years (Figure 1). The fall in the working-age population will reduce China’s labour input and will be a headwind for the production of goods and services. More retired people will reduce national savings. These are the effects that the 15th Five-Year Plan strives to manage.

Figure 1

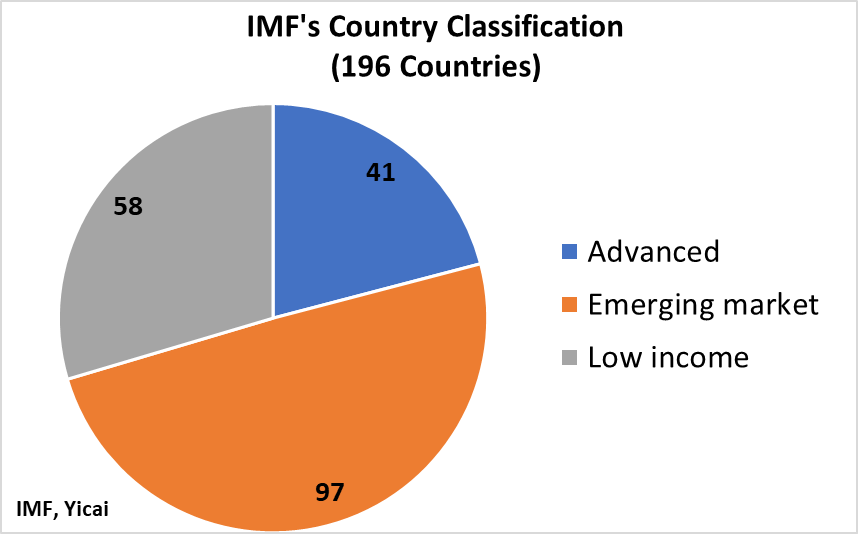

Along with its recommendations for the 15th Five-Year Plan, the Central Committee clarified its medium-term growth target of becoming a mid-level developed country (中等发达国家) by 2035. The Committee defined its objective as being able to enter the group that the IMF considers “advanced countries”. This is a difficult club to join. Currently, only 41 of the IMF’s 196 members are considered advanced countries (Figure 2). Moreover, in the last 20 years, only 12 emerging market countries became advanced countries and 5 of these were small economies like Andorra, Malta and San Marino.

Figure 2

The IMF’s classification is not based on strict criteria, “economic or otherwise” and has evolved over time. It is designed to facilitate analysis by providing a “reasonably meaningful method of organizing data.” Having high per capita GDP definitely seems to matter, but Saudi Arabia and Kuwait are not considered advanced countries, even though they are richer than Spain and Greece. While small island economies like Barbados and St. Kitts and Nevis have per capita GDPs that exceed that of Latvia, the poorest member of the advanced country group, they too are considered emerging market countries.

The Central Committee assumes, correctly I am sure, that if China would have had a per capita income of $20,000 in 2020, it would have been considered an advanced country. Thus, it targets achieving a per capita income of $20,000, in real terms, by 2035. This target implies an average annual GDP growth rate of 4.17 percent over the 15th and 16th Five-Year Plan periods.

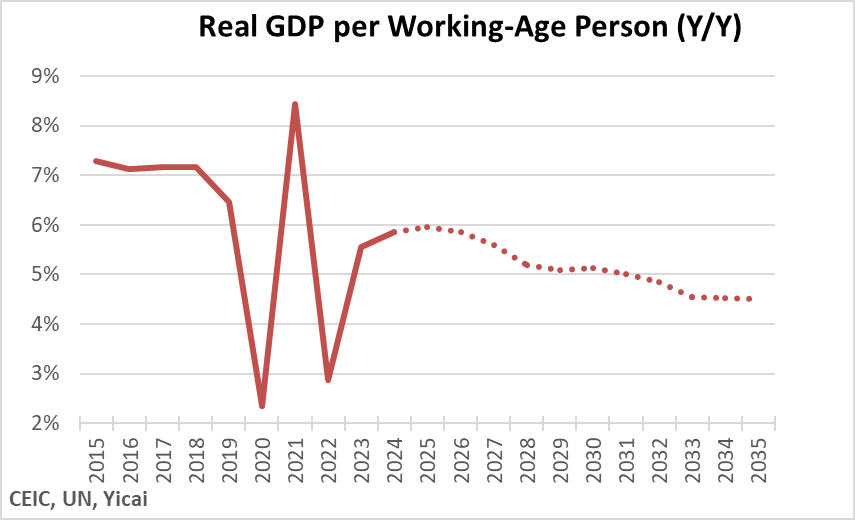

Knowing the profile for China’s working-age population and given the Central Committee’s growth projection, we can derive the evolution of productivity growth in terms of real GDP per working- age person (Figure 3).

This productivity growth was about 7 percent prior to the pandemic and is expected to be in the 6 percent range in the near term. It will then decelerate slowly and fall to 4.5 percent by 2035. Productivity growth at this rate, while significantly slower than over China’s past, would still be about twice as fast as the US is recording.

Figure 3

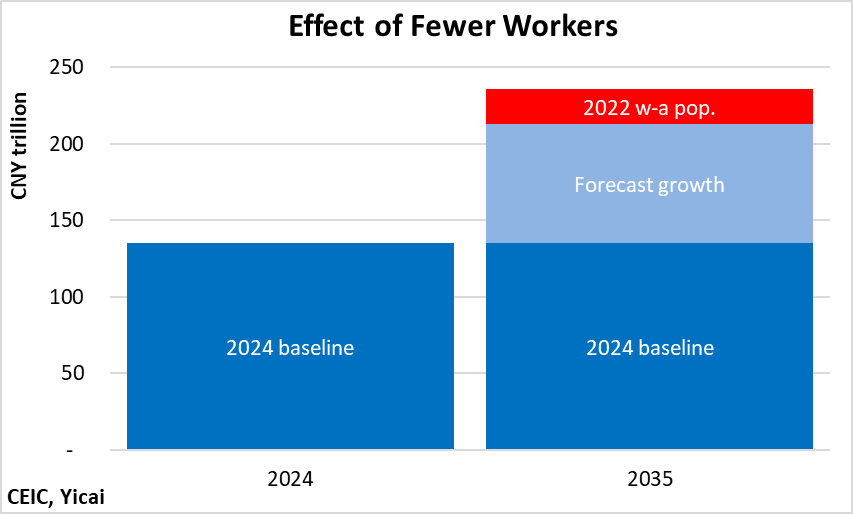

Armed with this estimate for the evolution of China’s productivity, we can construct a counter-factual to assess how much of a drag the decline in the working-age population will be on GDP growth. It’s simple to do, we just assume that the working-age population remains unchanged at its peak, 2022 level, and then multiply this number of workers by the productivity profile in Figure 3.

Figure 4 compares the counter-factual to the Central Committee’s scenario. The level of GDP last year was CNY 135 billion. We assume that the economy grows by 5 percent this year and then at an average annual rate of 4.17 percent from 2026 to 2035. This would result in GDP increasing to CNY 213 trillion in 2035. If the working-age population remained constant at its 2022 level, GDP would be an additional CNY 22 trillion (11 percent) higher.

Figure 4

What Figure 4 demonstrates is that average annual productivity growth of 5 percent over 2025-35 is more than enough to offset the 0.8 percent average annual decline in the working-age population.

Note that the 11 percent of GDP lost to fewer workers is the maximum effect. That is because we assume that the productivity paths are the same in both scenarios. However, economic theory suggests that the percent change in output should be smaller than the percent change in the number of workers (i.e. the marginal product of labour is less than 1). This implies that the productivity path for the counterfactual scenario should be somewhat slower than the one shown in Figure 3.

What this exercise shows is that to minimize the growth lost by unfavourable demographics, it is important to keep productivity high. And this, I believe, is the rationale for developing new quality productive forces (新质生产力).

New quality productive forces is an approach to increasing productivity based on innovation, investing in leading-edge high-tech sectors and promoting high-efficiency and high-quality output. It stresses breakthroughs in disruptive technologies, upgrading industries and fostering the sectors of the future.

The Central Committee foresees securing significant progress in new industrialization, informatization, urbanization and agricultural modernization. It anticipates decisive advances in integrated circuits, industrial machine tools, high-end equipment, basic software and advanced materials.

Like Wayne Grezky skating to where the puck is going to be, the Central Committee looks to capitalize on the industries of the future – quantum technology, biomanufacturing, hydrogen and nuclear fusion, brain-computer interfaces, embodied artificial intelligence and 6G mobile communications – as the new growth drivers.

China’s workforce will have to acquire the skills necessary to implement the new quality productive forces paradigm. The Central Committee speaks of building a labour pool with expertise of strategic importance and cultivating talent of all types, including strategists, leading scientists, outstanding engineers, master craftspeople and highly-skilled workers. Moreover, it looks to attract outstanding talent from around the world.

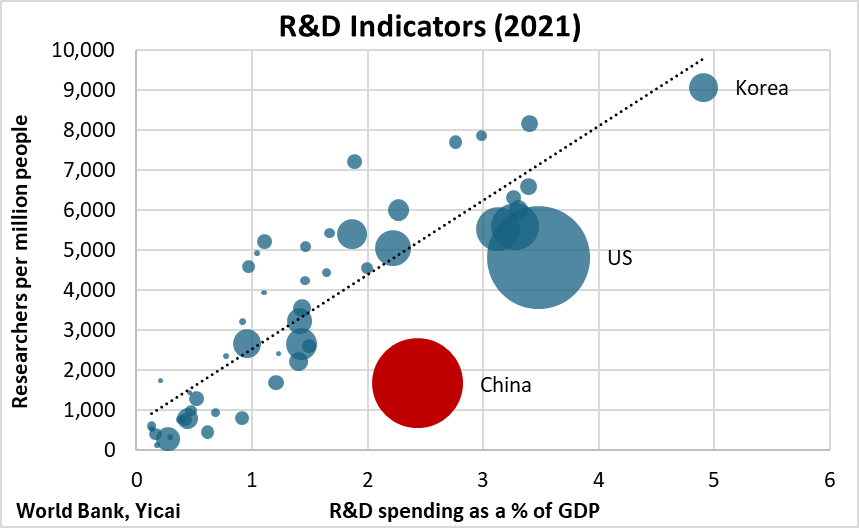

Improving human capital is crucial. In 2021, China spent the equivalent of 2.6 percent of GDP on research and development, a higher proportion than the European Union. However, compared to other economies, it employed many fewer researchers given the amount spent (Figure 5). This is why the Central Committee speaks of boosting China’s strength in education, science and technology and human resources.

Figure 5

The increase in the number of retired people – those who live off of their savings rather than saving themselves – should naturally result in higher consumption demand. The Central Committee wants to make sure that there are avenues for this demand to be actualized. In addition, by boosting employment, increasing incomes and raising the share of fiscal expenditures that goes to public services, it hopes to get working people to consume more too.

At 32 percent of disposable income, China’s household savings rates are very high. Across the OECD countries, the median household saving rate has been in the 6 to 8 percent range. If Chinese households save less, consumption could rise significantly.

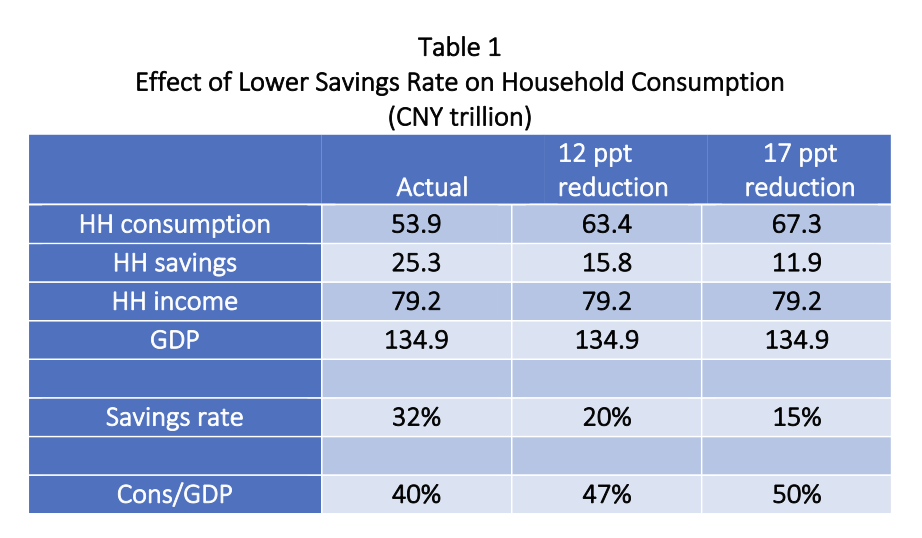

In 2024, household consumption was just 40 percent of GDP (government consumption was an additional 17 percent of GDP). If we apply the 32 percent household savings rate from the household survey to the national accounts estimate of household consumption, we can derive aggregate household income and savings (Table 1). We can then calculate, for 2024, how far the consumption to GDP ratio would increase as savings fell.

For example, a 17 percentage point fall in the savings rate, from 32 to 15 percent, would increase the consumption-GDP ratio by 10 percentage points. Even if this happened over a number of years, it would result in a significant rebalancing of GDP.

The Central Committee has proposed various initiatives to boost consumption. Most importantly, it proposes granting permanent urban residency to people who move to cities from rural areas. This would allow them to access basic public services where they actually live. The Central Committee also suggests steadily expanding the coverage of free education and exploring extending the length of compulsory schooling. To further spur spending, it supports abolishing unreasonable restrictions on the purchase of housing and motor vehicles. It even advocated staggering paid leave. This would reduce the crush of visitors to China’s famous attractions during the Golden Weeks and would encourage even more tourist spending.

It is important to remember that reducing savings and increasing consumption is not a free lunch for the Chinese economy. This is because the funds saved have been used elsewhere and are, presumably, funding some productive endeavour. There is, however, some small margin. China runs a current account surplus of some 2 percent of GDP. This represents savings that are lent abroad. Cutting lending to foreigners would not impact China’s GDP very much. But, a further reduction of savings would mean less funding for domestic investment and government spending.

For higher consumption to be growth enhancing and not simply a rebalancing of national spending, investment and government expenditure would have to become more productive – more bang for less buck – and that is exactly what the new quality productive forces are all about.