Is 5.5 Percent GDP Growth Too Optimistic?

Is 5.5 Percent GDP Growth Too Optimistic?(Yicai Global) March 11 -- On March 5, Premier Li Keqiang announced that the government is targeting real GDP growth in the 5.5 percent range this year. In the context of a rise in domestic COVID cases, ongoing difficulties in the property market and deep geopolitical uncertainty, many observers see this as an growth target.

The 5.5 percent target is higher than the 5.2 percent expected by the economists surveyed by and the 4.8 percent forecast by the International Monetary Fund. Several analysts believe that the government will have to undertake significant stimulus to achieve its goal.

I want to present a contrarian view. Given the extent to which growth last year was constrained by tight macroeconomic policies, it is easy to underestimate the Chinese economy’s underlying momentum.

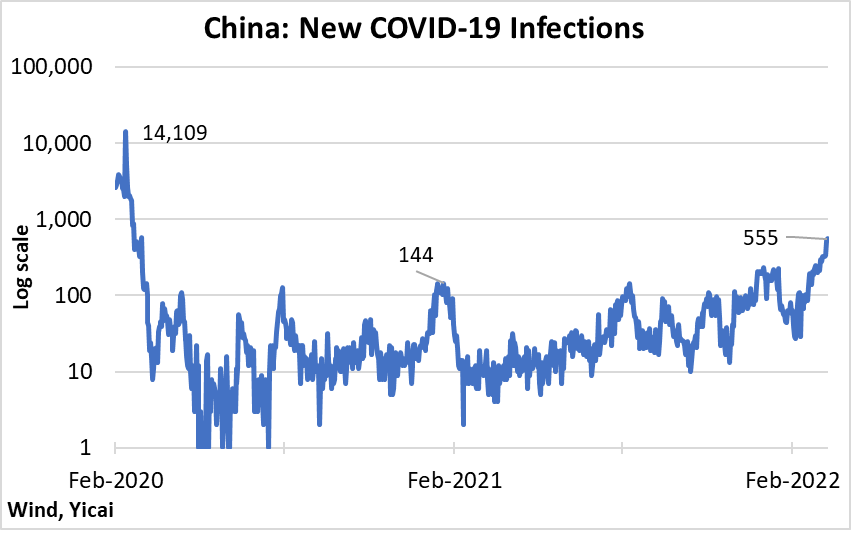

A growth rate of 5.5 percent is not particularly strong (Figure 1). Looking through the pandemic-induced volatility in 2020-21, growth averaged 5.2 percent. As China approaches the technological frontier, there has been a slow and steady decline in its GDP growth and 5.5 percent appears to be in line with the deceleration recorded in previous years. While 5.5 percent would represent an acceleration from the 4.0 percent growth recorded in the four quarters to 2021Q4, it is slower than the 6.6 percent growth between 2021 Q3 and 2021 Q4 (at annual rates).

Figure 1

Last year, the government targeted growth above 6 percent. That target was widely seen as an easy-to-meet low bar, with most analysts predicting growth in the 8 percent range. But the 6 percent target sent two important messages.

First, it indicated that 6 percent was the minimum rate of growth that the government would tolerate and that macroeconomic policy would become more supportive if growth looked to slow below 6.

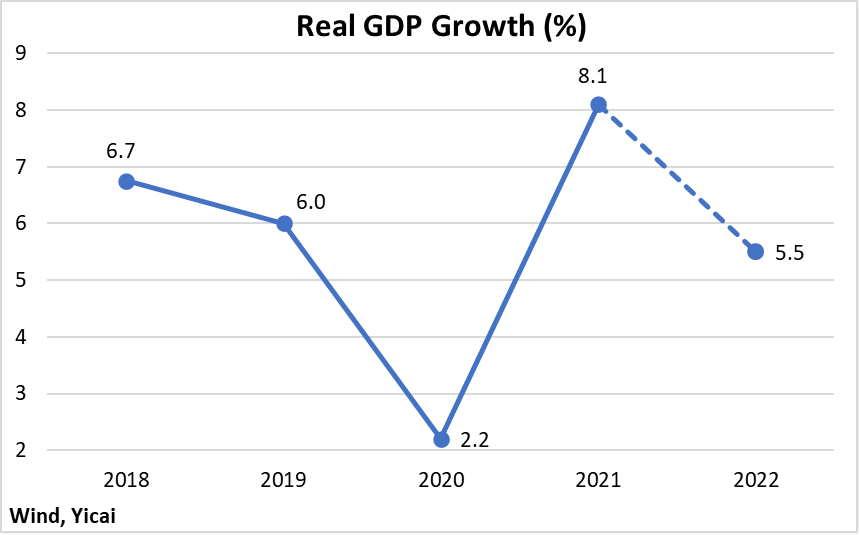

Second, and more importantly, the 6 percent growth target indicated that the government was hoping to unwind some of the powerful stimulus it provided in 2020 to offset the economic effects of the pandemic. This stimulus was reflected in the sharp increase in China’s indebtedness. Between December 2019 and September 2020, China’s macro leverage ratio rose by 25 percent of GDP (Figure 2). During these nine months, this broad measure of the country’s indebtedness increased by more than it had over the previous 4 years!

Figure 2

As the pandemic abated, macroeconomic policy turned to scaling back its stimulus and, between September 2020 and December 2021, tight financial policies led to a 7 percent of GDP reduction in the macro leverage ratio. In particular, the leverage of the non-financial corporate sector fell by close to 10 percent of GDP, with property developers being particularly hard hit. In the absence of this financial policy tightening, growth would have certainly been much stronger last year (albeit at the cost of greater financial risk).

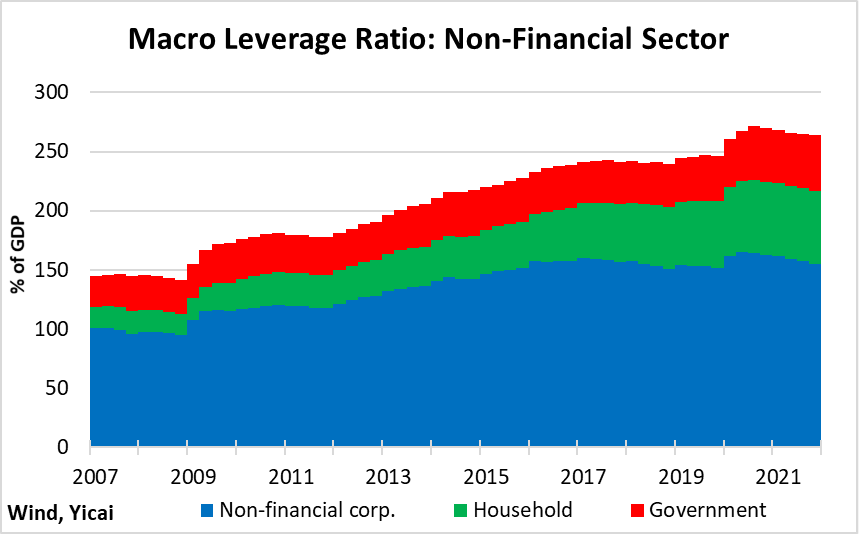

Credit policy will be more supportive of growth this year than it was in 2021. In his report to the National People’s Congress, Premier Li said that the macro leverage ratio will stabilize and aggregate credit will grow at the same pace as nominal GDP. This indicates that there is no need for further deleveraging. Credit growth has picked up after having tightened significantly in 2021 and one-month interest rates have fallen about ½ a percentage point below where they were before the pandemic (Figure 3).

Figure 3

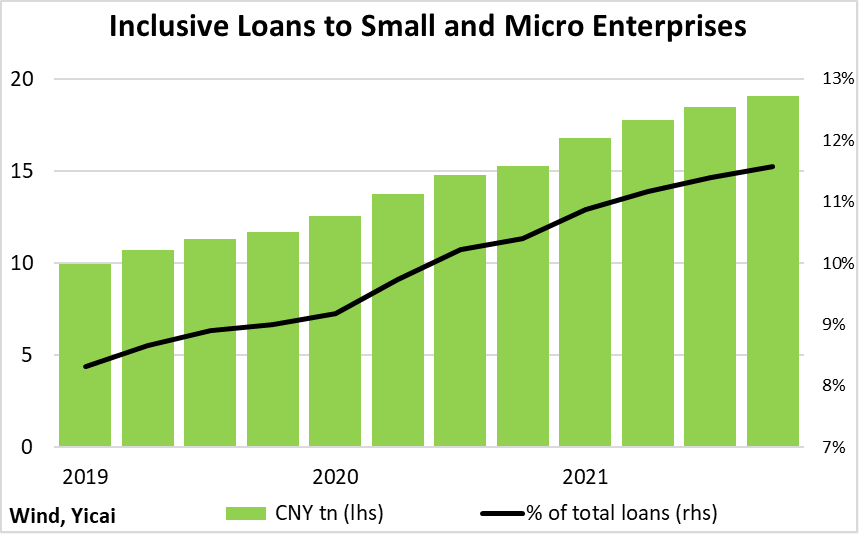

In a , Guo Shuqing, the Chairman of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission, indicated that credit policy will support the economy by targeting small- and micro-enterprises. Loans to these firms have grown rapidly: from CNY 10 trillion in 2019Q1 to CNY 19 trillion as at the end of 2021 and they now account for 11.6 percent of all loans outstanding (Figure 4). Still, only 30 percent of small firms are able to obtain loans and Guo indicated that banks would lever digital technologies to improve access to financial services.

Figure 4

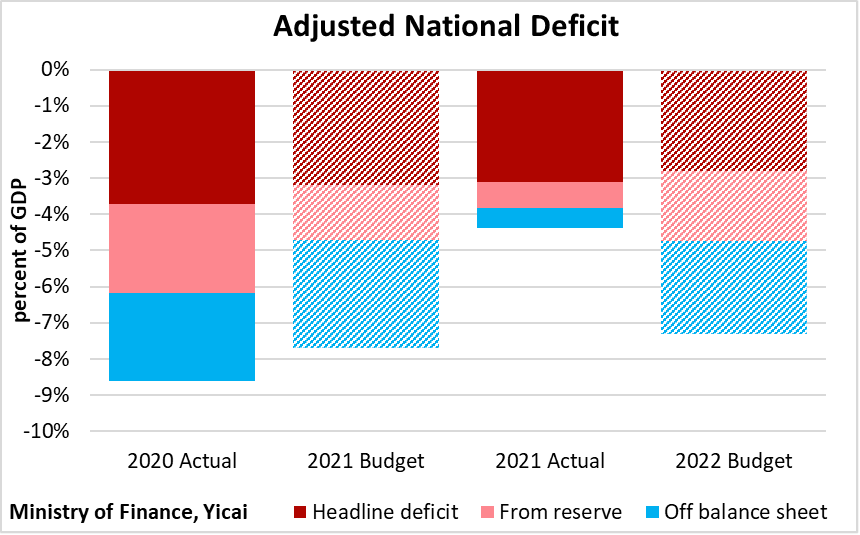

The of the government’s fiscal outturn for 2021 and outlook for 2022 indicated that the headline deficit came in at 3.1 percent of GDP, as budgeted. The headline deficit was somewhat smaller than recorded in 2020 (3.7 percent of GDP), but the details in the report show just how tight fiscal policy was last year (Figure 5).

Figure 5

The government reports its fiscal accounts on an accrual basis. In recent years, it has drawn on its stabilization fund and has accounted for these drawings as revenue. The drawing in 2020 was particularly large (2.5 percent of GDP) while the one last year was much more modest (0.7 percent of GDP).

When the government finances its expenditures through taxes, it essentially sucks some spending power out of the private economy. When it uses the money in its “bank account” to pay, the effect on private spending is much more modest.

The “cash deficit” which considers drawing on the stabilization account a “funding” rather than a “revenue” item is a better representation of fiscal policy’s macroeconomic impact. In 2021, the cash deficit fell to 3.8 percent of GDP, from 6.2 percent in 2020 and suggests a much tighter fiscal policy than the headline numbers do.

The details of the 2021 budget outturn indicate a second source of fiscal tightening. In addition to the government’s revenue and expenditures, it reports the accounts of three classes of off-balance sheet funds: social security, the capital budget of state-owned firms and other government-managed funds. I have aggregated these off-balance sheet items in Figure 5. Their deficit is dominated by local government-managed funds, which account for real estate-related activities.

While local governments typically receive large sums for selling the rights to develop property, they also incur significant expenses. In developing unoccupied land, these expenses are related to providing roads, utilities and other services. In re-developing occupied urban land, they are related to compensating existing residents who must move.

In 2021, the deficit of the off-balance sheet funds was 0.5 percent of GDP, down from 2.5 percent of GDP in 2020. This drop likely reflects a slowdown of construction activity and represents another area in which fiscal policy was much tighter last year than it was in 2020.

In sum, what I call the “Adjusted National Deficit” was 4.4 percent of GDP in 2021, down from 8.5 percent of GDP in 2020. This 4 percent of GDP reduction represents a very significant fiscal tightening.

Looking to this year, Premier Li’s report stated that the headline fiscal deficit for 2022 would fall to 2.8 percent of GDP from the 3.1 percent recorded in 2021. While this suggests a mild tightening, the details of the budget outlook indicate that fiscal policy will be much more supportive than last year.

In particular, CNY 2.3 trillion is to be transferred to the budget from the stabilization fund. This is 1.2 trillion more than was transferred in 2021. In addition, the deficit of the off-balance sheet funds is budgeted to rise to 2.6 percent of GDP from 0.5 percent of GDP in 2021, with the increase coming from local government-managed funds. Overall, the “Adjusted National Deficit” implicit in the budget for 2022 will rise to CNY 8.8 trillion from CNY 5.0 trillion in 2021: an increase of 3 percent of GDP. Should the fiscal accounts evolve as budgeted, they would provide significant support to the economy.

While the normalization of macroeconomic policy sets the stage for 5.5 percent growth this year, the economy does face risks.

First, there is no telling how much the conflict in Ukraine will destabilize the global economy. Nevertheless, China seems well-insulated. Its trade with Russia and Ukraine represents 2.4 percent and 0.3 percent, respectively, of China’s overall trade. The commodities it imports from these countries can likely be replaced by other suppliers. And international demand for Chinese-made products remains robust. After rising by 30 percent last year, worldwide exports are up 16 percent year-over-year in January-February this year.

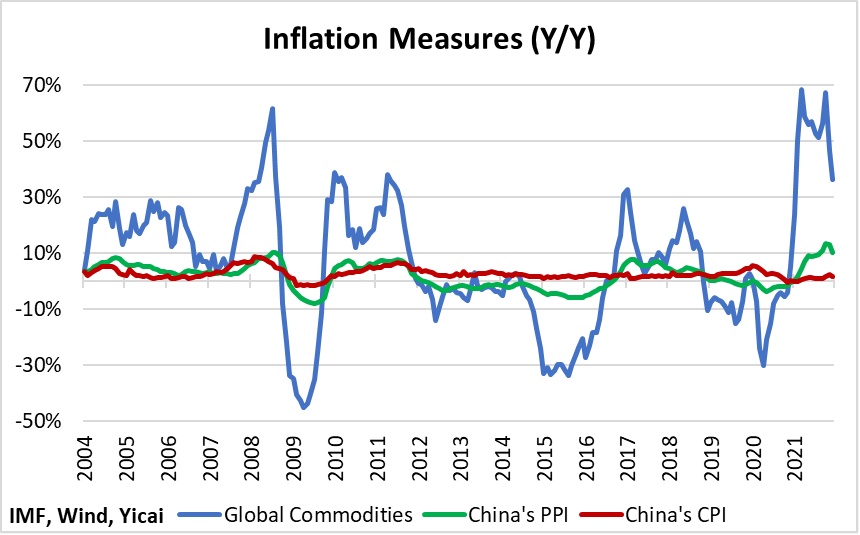

Second, China is a major commodity importer and the conflict has led to a sharp increase in the price of oil and other key resources. However, commodities only comprise a small part of Chinese-made goods’ value-added. Thus, a 10 percent increase in global commodity prices typically results in increases of 1.7 and 0.3 percent in Chinese producer and consumer prices (Figure 6).

Figure 6

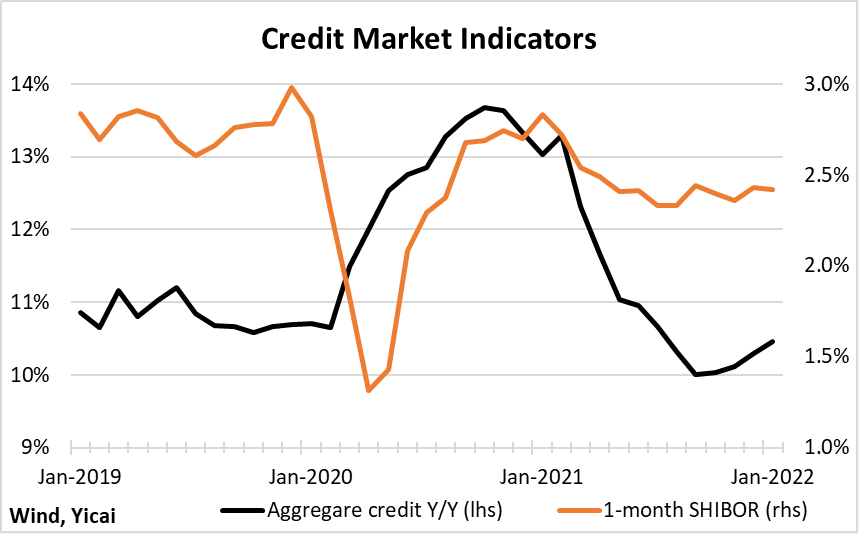

The third risk facing the economy this year comes from the evolution of the pandemic. On March 10, new infections hit 555, their highest level in two years (Figure 7). There have been targeted sealings of communities across the country. Eleven of the 42 children in my daughter’s Grade 4 class were unable to attend school this week. None of them were infected, although they may have been in close contact with those who were. The entire student body will take COVID tests tomorrow.

The strong measures implemented to preserve public health will certainly weigh on consumption this year. Already, I see fewer people in restaurants and cafes. However, it is worth noting that had China’s COVID-19 mortality rate matched that of the US, about four million – instead of a few thousand – Chinese people would have died. To be sure, some things are more important than GDP.

Figure 7