China’s Evolving Lending to Middle- and Low-Income Countries

China’s Evolving Lending to Middle- and Low-Income Countries(Yicai) Dec. 5 -- On November 24, the Office of the Leading Group for Promoting the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) published its for the next ten years.

Looking ahead, it said, the BRI will be characterized by “high-quality development”. In particular, it will focus on smoother and more efficient connectivity, enhancing cooperation, elevating peoples’ gain and fulfilment, supporting the further opening of the Chinese economy and popularizing the vision of a global community with a shared future.

China’s lending to middle-income countries (MICs) and low-income countries (LICs) has undergone dramatic changes in recent years. These changes are poorly understood. Those who want a clear picture of China’s place in development finance are well-served by the and database recently released by AidData. AidData is an international development research lab housed at in Williamsburg, Virginia.

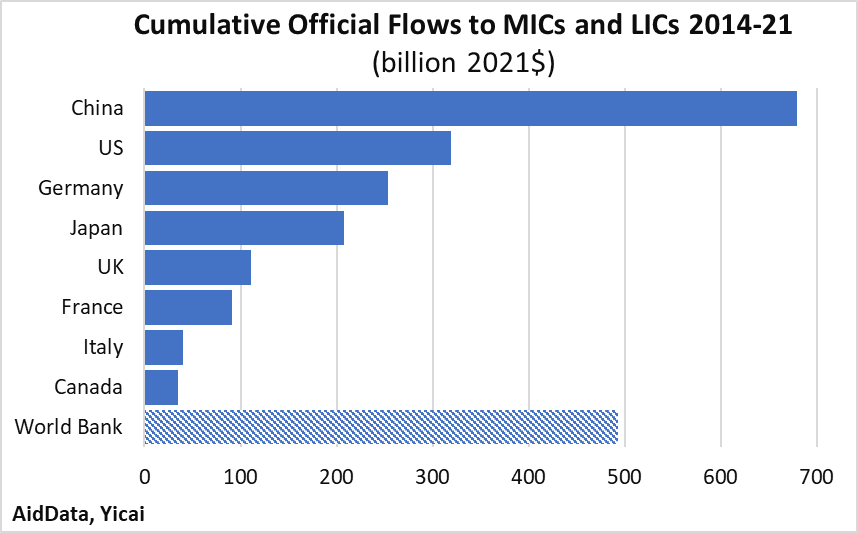

According to AidData’s broad measure of overseas lending, China was, by far, the biggest source of international development finance between 2014 and 2021. Its cumulative commitments to MICs and LICs totalled $680 billion. Over the same period, the US only lent $319 billion. In fact, China provided one-third more finance than the World Bank, the largest multilateral lender (Figure 1).

Figure 1

According to former PBOC Governor , China’s ability to supply infrastructure projects derives from two comparative advantages. First, Chinese firms have deep domestic experience in the construction of roads, railways, ports, airports and power grids as well as in the manufacture of power generation equipment. Second, China’s high national savings rate makes it easy to tap domestic markets for the funds to finance infrastructure projects abroad.

China’s willingness to supply infrastructure in MICs and LICs comes from its need to secure a diversified supply of energy, minerals and other natural resources. These projects help develop the resources and the means needed to transport them to China and other markets.

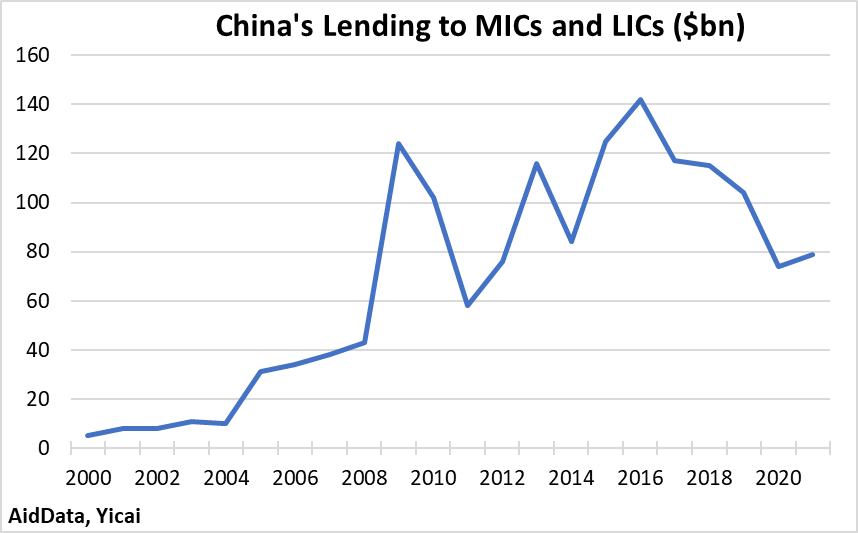

China’s lending to LICs and MICs has fallen off in recent years. From a peak of $140 billion in 2016, its commitments dropped to some $80 billion in 2021 (Figure 2). Nevertheless, China retained its leading position in development finance. In 2021, no G7 country lent more than $61 billion and the World Bank only provided $72 billion.

Figure 2

The recent fall in China’s lending to MICs and LICs results, in large part, from their debt service difficulties. These difficulties arose from an unfortunate confluence of events.

The grace periods on Chinese loans are expiring. While the infrastructure projects come on stream, the borrowers typically make small debt service payments. The payments increase after the grace period expires. By 2020, 40 percent of China’s loans to MICs and LICs required the repayment of principal. AidData estimates that the share rose to 55 percent this year and it will increase to 75 percent by 2030.

This means that the MICs and LICs have had to make bigger debt service payments to China when interest rates are rising, the US dollar is strengthening and global growth is slowing. Many borrowers have been unable to do this and AidData finds 98 incidents of Chinese debt being rescheduled in 2020 and 2021.

As a consequence, China’s focus has shifted from financing infrastructure to preventing sovereign defaults among some of its most important BRI partners. Infrastructure’s share in China’s lending to MICs and LICs has fallen from 65 percent in 2014, to 50 percent in 2017 and 31 percent in 2021. Over the same period, emergency crisis lending has become more important, rising from 5 percent in 2013 to 58 percent in 2021.

The PBOC is the most important source of emergency lending and, by 2020, it lent more to MICs and LICs than any other Chinese institution. The PBOC offers these emergency loans to borrowers with weak credit ratings and low levels of international reserves. The more credit-worthy borrowers have continued to receive infrastructure project loans from other lenders.

As a result, the share of new loans in dollars fell from 93 percent in 2013 to 44 percent in 2021, while that of CNY loans rose from 6 percent in 2013 to 50 percent in 2021. Loans in CNY can be used to repay Chinese creditors. Moreover, the IMF accepts CNY, which is a currency in the Standard Drawing Rights basket, in repayment of its claims on member countries.

China has employed several strategies to mitigate the financial risks of its MIC and LIC lending.

First, it has increasingly demanded collateral for its loans. Between 2000 and 2017 only 42 percent of China’s loans were collateralized. The share rose to 56 percent, on average, in the 2018-21 period. By 2021, nearly three-quarters of China’s overseas lending to LICs and MICs was collateralized.

Collateral often takes the form of deposits in an escrow account. These deposits typically cover 1 to 3 semi-annual principal and interest payments. They are usually equivalent to 5-10 percent of the face value of the loan supported by the escrow account.

Second, Chinese lenders are generally willing to defer principal and/or interest payments for several years, thereby providing short-term cash flow relief. However, they are generally unwilling to accept significant financial losses in net present value terms.

Third, the terms of the loans have become more stringent. Interest rates have risen modestly but the weighted average repayment period has been shortened from 11 to 6 years. There has also been a transition from fixed- to floating-rate loans, which shifts interest rate risk from the lender to the borrower.

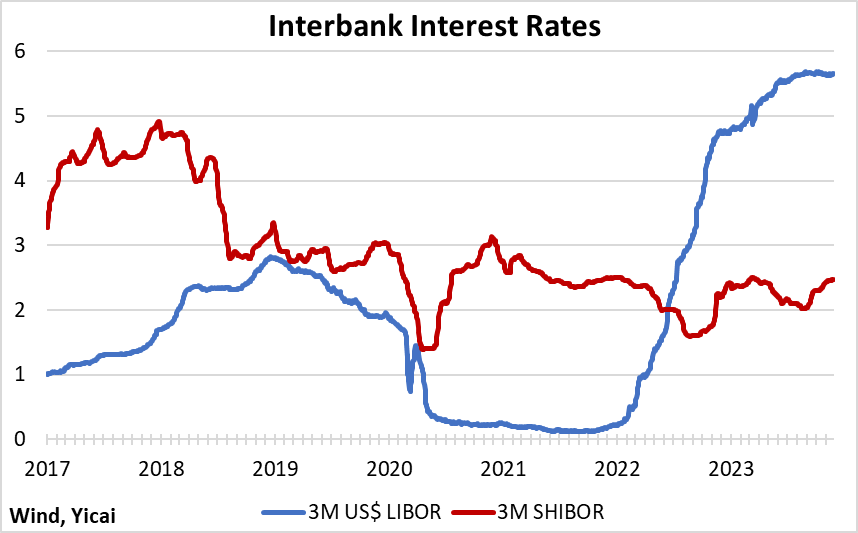

Consistent with the evolution to CNY lending, SHIBOR has replaced US$ LIBOR as the reference interest rate. Indeed, in 2008, none of the variable interest rate loans to MICs and LICs were priced off of SHIBOR. By 2021, SHIBOR was the reference rate for 70 percent of them.

The shift to SHIBOR pricing has been a boon for borrowing countries as three-month US$ LIBOR rates have risen from close to zero in late 2021 to over 5½ percent recently while three-month SHIBOR rates have been fairly stable (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Fourth, Chinese lenders have also mitigated financial risks by pooling exposures. Early on, loans were bilateral: a single lender to a single borrower. Over time, issuing credit became more collaborative, with syndicated loans becoming more popular. By 2021, 50 percent of China’s non-emergency lending program in LICs and MICs consisted of syndicated loans.

In addition to managing the financial fallout from the deterioration in MIC and LIC creditworthiness, Chinese lenders are also actively dealing with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) risks.

To determine if a Chinese-financed infrastructure project presented a significant ESG risk, AidData highlighted those that were located in environmentally or socially sensitive areas; those that were vulnerable to political capture and manipulation; and those that employed sanctioned contractors. In addition, it identified projects that encountered significant ESG challenges before, during, or after their implementation.

Between 2000 and 2021, China financed 4800 infrastructure projects worth $825 billion. AidData found that 1693 of these projects, valued at $470 billion, were exposed to significant ESG risks.

These risks did not escape the notice of Chinese policymakers, who responded by putting increasingly stringent safeguards in place.

In 2017, the China Banking Regulatory Commission required the China Development Bank and the China Eximbank to implement more robust environmental and social risk management procedures. In 2021, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange announced that it would prioritize adopting the ESG criteria used by the multilateral development banks.

Chinese policymakers have also taken many practical steps to mitigate ESG risks. Chinese financial institutions with the weakest ESG safeguards were discouraged from lending while the financing of those that put a greater emphasis on ESG was ramped up. Chinese lenders have outsourced risk management by participating in coordinated finance with international institutions. Finally, exposures to high-risk countries were wound down and those to low-risk countries increased.

As a result of these measures, AidData finds that China’s ESG risk prevalence rate – the annual percentage of its infrastructure project portfolio with significant ESG risk exposure – fell from 65 percent in 2013 to 33 percent in 2021.

The application of more stringent ESG safeguards has not compromised Chinese firms’ ability to rapidly construct infrastructure projects.

AidData finds that projects with strong ESG safeguards were typically completed in 3.2 years. Those without the safeguards were only completed 8 days faster. It is worth noting that it takes the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank 6 years, on average, to complete their infrastructure projects.

There is a narrative out there that Chinese lending to MICs and LICs has been counter-productive because it pushed them into .

In the case of sub-Saharan Africa, the has been clear that Chinese lending “… has not been the principal contributor to the region’s public debt surge in the past 15 years.”

AidData’s report also helps reveal the true nature of China’s lending operations and it goes a long way toward dispelling misconceptions. It shows that China remains a key source of finance for MICs and LICs. Moreover, China is delivering large-scale infrastructure projects with increasingly robust ESG safeguards but without the lengthy implementation delays that often plague the projects backed by G7 countries or the multilateral development banks.