China’s Emissions Peak: What Are the Implications?

China’s Emissions Peak: What Are the Implications?(Yicai) July 9 -- China’s dual carbon goals are ensuring emissions peak before 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. Recent analysis published by Carbon Brief suggests that China’s CO2 emissions peaked in 2024, six years earlier than foreseen. Carbon Brief is a UK-based website covering the latest developments in climate science, climate policy and energy policy. Their finding of emissions peaking, well before 2030 should come as no surprise to those who follow its research.

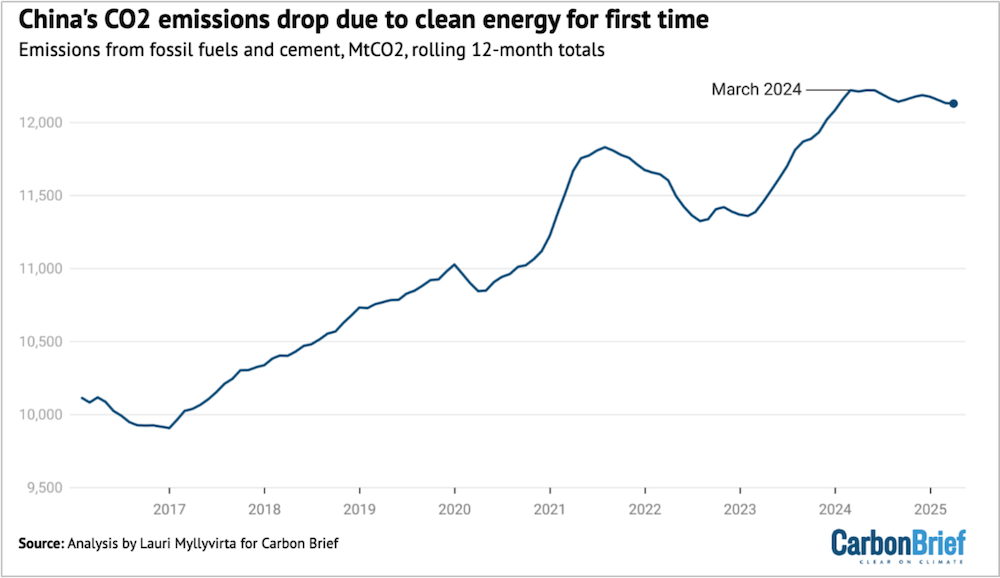

China’s emissions had previously peaked in mid-2021 and then fell through early 2023 (Figure 1). This reflected a pandemic-related, temporary drop in energy demand. As the economy recovered, emissions continued to rise and then reached new highs. However, Carbon Brief believes that the peak realized in March 2024 will be unsurpassed as a result of a structural increase in clean energy supply. It estimates that emissions in the first quarter of 2025 fell by close to 2 percent from the same period in 2024.

Figure 1

Electricity generation is the largest source of China’s emissions, accounting for some 60 percent of the total. Massive investments in solar, wind and nuclear power generation have reduced the power sector’s emissions even though China’s demand for electricity is still growing.

In the first quarter, investments in clean energy allowed for a 5 percent year-over-year drop in thermal (coal and natural gas) electricity generation while meeting a 3 percent increase in electricity demand. As a result of a more environmentally-friendly power generation mix, the sector’s emissions fell by almost 6 percent from the first quarter of 2024.

China does continue to invest in new coal-fired power plants. The foreign media often point to these projects as a sign that China is not serious about climate change, but the new plants are more efficient and are an integral part of its CO2 reduction plan. Carbon Brief notes that, in the first quarter, the amount of coal needed to generate a given amount of electricity was down close to 1 percent year-over-year.

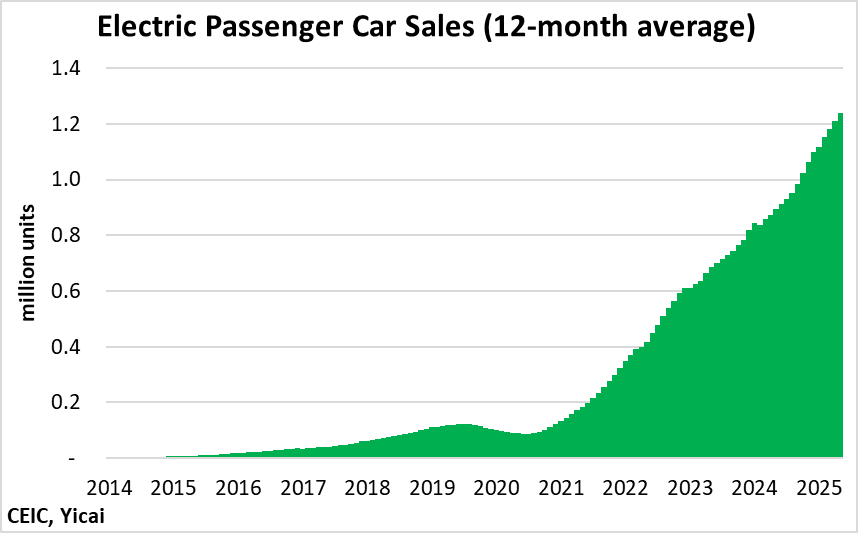

The transportation sector accounts for about 9 percent of China’s emissions. As electric vehicles become more popular, emissions in this sector are also falling. In the 12 months to May, average monthly sales of electric cars surpassed 1.2 million units. This is up from only 200,000 units in May 2021 (Figure 2). The transition from diesel to liquified natural gas-powered trucking is also playing a role in lowering transportation sector emissions.

Figure 2

Carbon Brief notes that the coal-to-chemicals industry is expanding rapidly, as part of China’s response to its dependence on foreign oil and gas. While emissions from the coal-to-chemicals sector are on the rise, those from steel and cement have been limited by the prolonged downturn in the property market.

Still, Carbon Brief thinks that, even after these cyclic factors have worked themselves out, emissions are unlikely to increase. This is because the growth in clean power generation in the first quarter exceeded the long-term increase in demand.

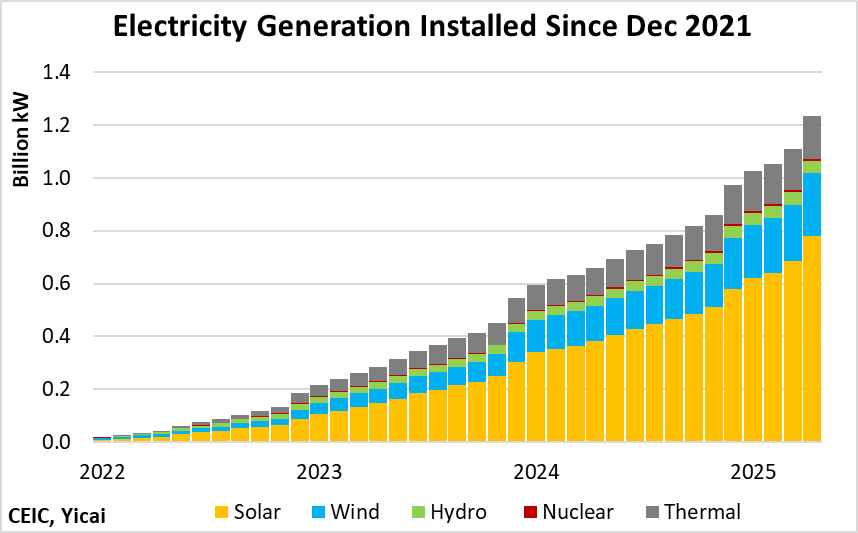

The clean energy investments made in the first quarter are part of a longer-term trend. Since the end of 2021, China has added more than 1.2 billion kW, increasing its electricity generating capacity by more than 50 percent. Solar and wind power accounted for 83 percent of these installations (Figure 3). New thermal power plants represented just 13 percent.

Figure 3

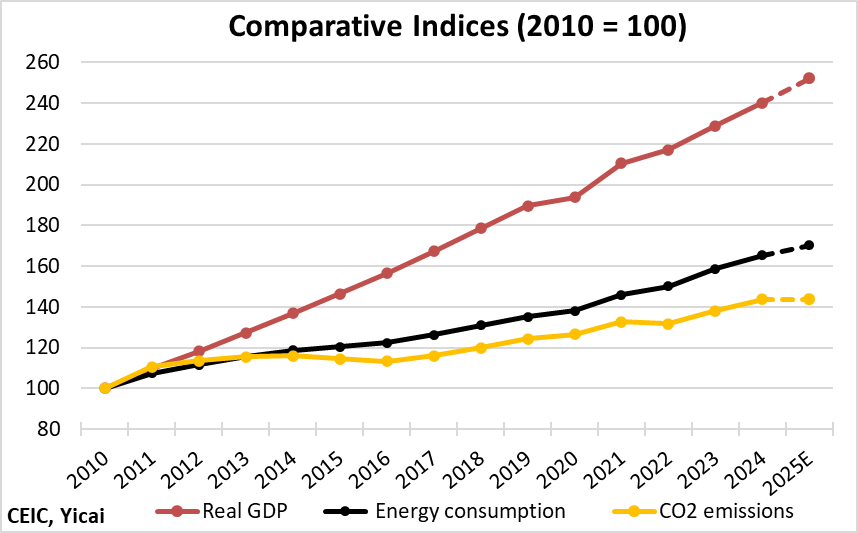

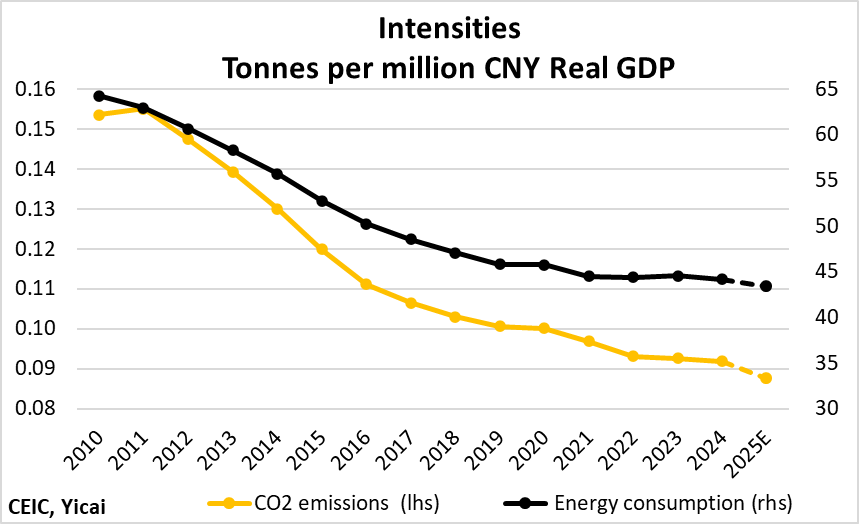

China is working on two margins to achieve its emission reduction goals: it wants to reduce both the energy intensity of GDP and the carbon intensity of its energy supply. Over the last 15 years, it has made significant progress on both fronts. Assuming that GDP grows by 5 percent this year, carbon emissions are flat at 12.4 billion tonnes and energy demand rises by 3 percent, then China’s real GDP will have grown by 150 percent, while energy consumption will only be up 70 percent and carbon emissions will rise just 44 percent (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Between 2010 and 2019, both energy and emissions fell rapidly as a share of real GDP (Figure 5). Since then, the energy intensity of China’s economy has only declined modestly. Most of the gains in emission reduction have come from investments in a less carbon-intensive energy mix.

Figure 5

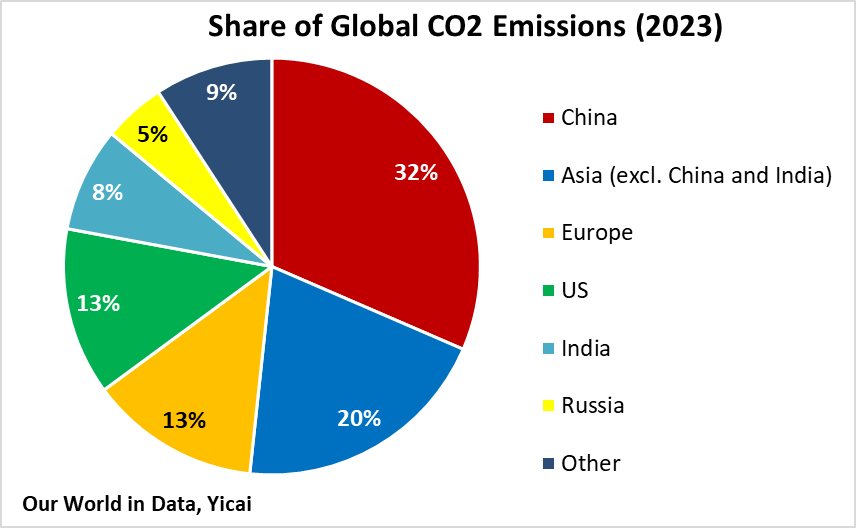

Even if its emissions have peaked, China remains, by far, the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide. In 2023, it accounted for close to one-third of the global total, about the same as Europe, the US plus Russia (Figure 6).

Figure 6

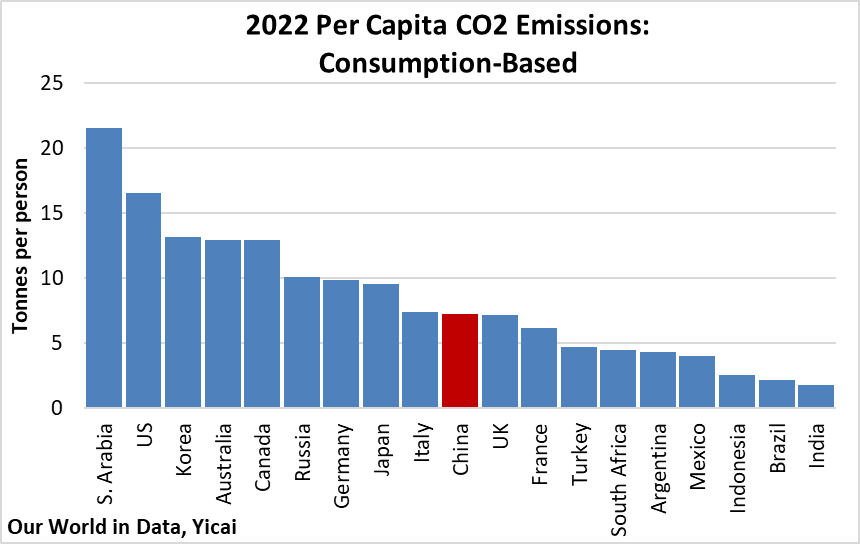

China is not a large emitter because its people lead particularly carbon-intensive lifestyles. Its per capita emissions are moderate compared to its G20 peers (Figure 7). When looked at on a consumption basis – which adds the emissions that a country “imports” and subtracts what it “exports” – per capita emissions in China are 7.2 tonnes per person. This puts China between the UK and Italy. China’s per capita emissions are about three-quarters of the level of Germany and Japan. Moreover, they are only 44 percent of US per capita emissions. Thus, the first key implication of China’s emissions peaking early is that this stabilization is occurring at a relatively low per capita level, at least for a major industrial country.

Figure 7

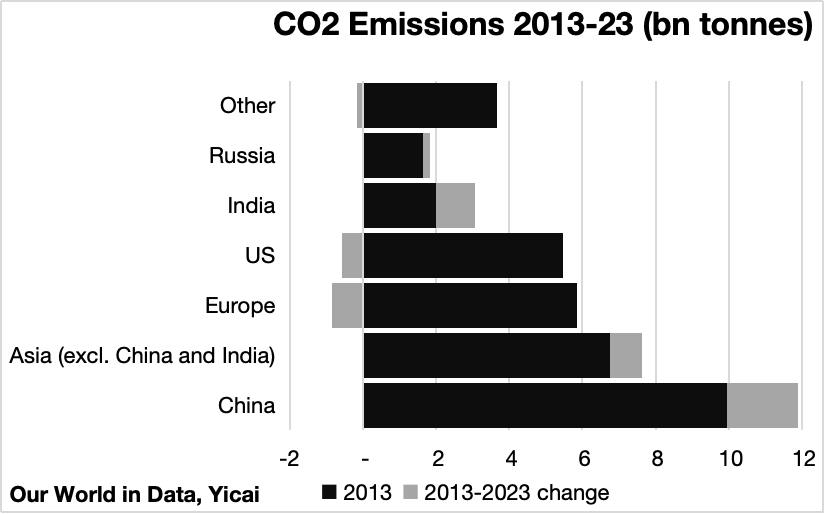

The second key implication of China’s early peak is that global emissions will slow significantly. Figure 8 shows how emissions have evolved between 2013 and 2023 across the major geographic regions. During that decade, emissions rose the most in China, followed by India and then the other Asian countries. They also increased modestly in Russia. In contrast, emissions fell in Europe, the US and “other” countries. Between 2013 and 2023, global emissions rose by 2.5 billion tonnes, of which 1.9 billion were emitted by China. If China’s emissions have peaked, then the major source of global emissions growth has been eliminated.

Figure 8

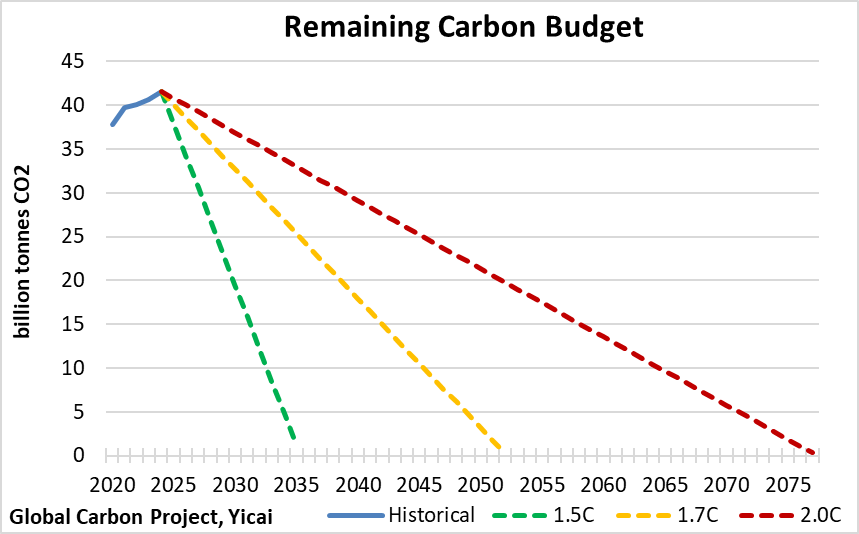

In describing the challenges of climate change, scientists talk about the global carbon budget. This is the maximum amount of carbon dioxide that can be emitted while limiting global warming to a particular level. For example, from 2025 on, global emissions need to be less than 215 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide in order to keep warming to 1.5 degrees. That’s only 5 years at 2024 emission levels. Given current trends, there is only enough carbon budget left for 14 years before warming exceeds 1.7 degrees and 26 years before it exceeds 2.0 degrees.

In order for us to respect the carbon budget, the world has to rapidly decrease emissions. Figure 9 illustrates the paths emissions would have to take, from their 2024 actual level, to keep global warming to 1.5, 1.7 and 2.0 degrees.

Figure 9

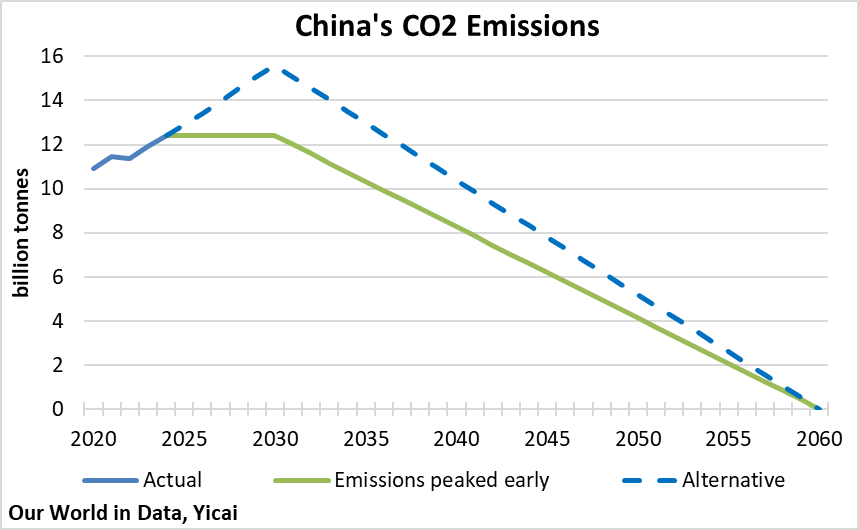

If China’s emissions have peaked 6 years early, then it is helping to stretch the global carbon budget. To illustrate this, consider two scenarios. In the early peak scenario, China’s emissions are flat at 2024 levels to 2030 and then decline in a linear fashion to zero emissions in 2060. In the alternative scenario, we assume no improvement in China’s carbon intensity. Emissions grow at the same rate as GDP to 2030. We use the IMF’s forecasts for China’s GDP growth from its most recent World Economic Outlook. From there, emissions decline linearly to 2060 (Figure 10).

Between 2025 and 2060, the early peaking of China’s emissions saves 57 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide relative to the alternative scenario (this is the difference between the green and dashed blue lines in Figure 10). This savings is 40 percent more than global emissions in 2024. It also stretches the carbon budget to keep global warming at 1.7 degrees by 10 percent.

Figure 10

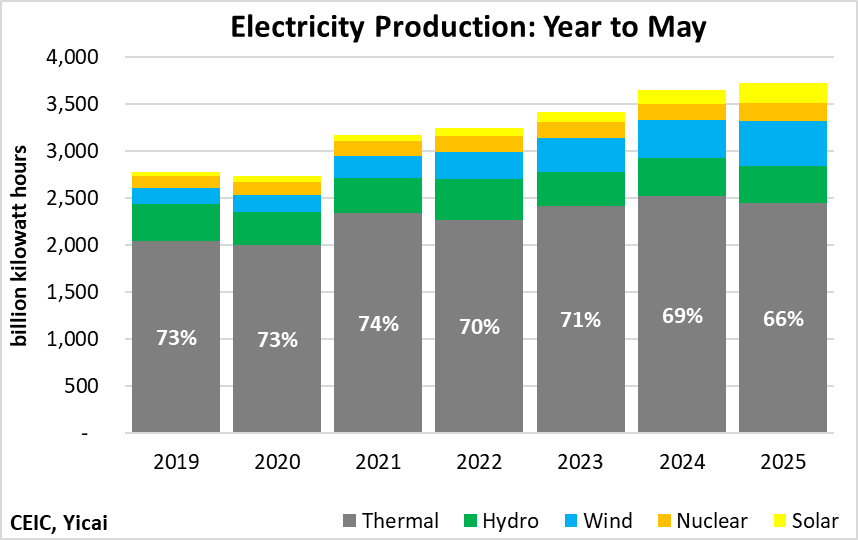

Looking at the data through May, it seems reasonable to expect emissions to fall this year. Electricity production is up 2 percent from the first five months of 2024. However, thermal-powered generation is down 2 percent. In contrast, solar-powered generation is up 41 percent while electricity coming from wind power is up 17 percent. So far this year, 66 percent of China’s electricity was generated from thermal sources. This is a steep reduction from its share in previous years (Figure 11).

Figure 11

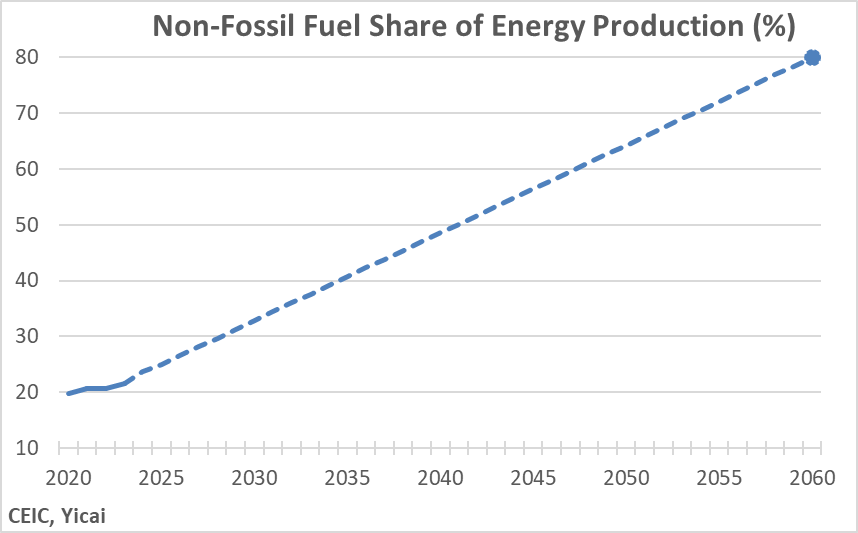

While recent results are encouraging, we are at the beginning of a decades-long process during which China will continue to invest heavily in green energy. According to China’s long-term emission strategy, non-fossil fuels’ share in energy consumption must rise to 80 percent by 2060 (Figure 12).

Figure 12

Even as some countries turn away from acting on climate change, China has emerged as the clear leader in clean energy. What appears to be an early peak in China’s emissions has three key implications: stabilization is occurring at a relatively low level of per capita emissions, global emissions will now grow more slowly and the constraints of the global carbon budget have been somewhat relaxed. While there is still a long road to travel, China’s early success is certainly good news for everyone.