Sweating Through A Heat Wave: Pondering Renewable Energy

Sweating Through A Heat Wave: Pondering Renewable Energy(Yicai Global) July 16 -- It is hot outside.

Shanghai’s temperature averages 31 degrees in July. But for the last ten days, the highs have been in the upper 30s, with the thermometer hitting 40 every day this week.

As a Canadian, I have always found Chinese summers to be scorchers. In the 1980s, when I was studying in Tianjin, no one’s home had air conditioning. People avoided their stuffy apartments by sitting outside late into the night or even by sleeping in the streets. To beat the heat, folks relied on the chilled slice of watermelon, the electric or handheld fan and a glass of cooling tea(凉茶).

These days, air conditioning is widespread and my apartment is very comfortable. But then I get to thinking about all the energy that needs to be generated to cool me off and how the carbon released contributes to global warming and I wonder how sustainable my comfort is.

Clearly, the path to sustainability requires a reduced reliance on fossil fuels. The question is how fast we can travel along that path.

It was with this question in mind that I read through China’s 14th Five-Year Plan for Renewable Energy. The Plan, which was released last month, was co-authored by nine ministries and agencies including the National Development and Reform Commission, the National Energy Board, the Ministry of Finance and the Department of Natural Resources.

The Plan sets targets for the 2021-25 period that provide near-term guidance on how China will achieve the “nationally determined contributions” to which it committed itself as part of the Paris Agreement.

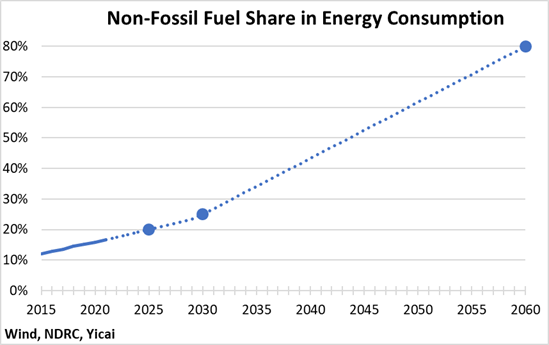

China’s highest-level commitment was to have carbon emissions peak before 2030 and to become carbon neutral by 2060. In support of these objectives, China pledged to increase the share of non-fossil energy in total energy consumption to 25 percent by 2030.

According to the Plan, non-fossil fuels will constitute 20 percent of energy consumption in 2025. In 2021, they accounted for 17 percent of China’s energy consumption. Over the period 2020-2025, non-fossil fuels’ share will rise by 4 percentage points. The planned increase is the same as the one actually recorded during the previous five-year period.

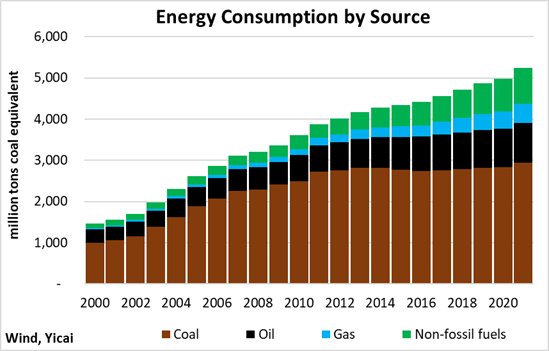

While fossil fuels’ share in the energy mix has declined over the last two decades, fossil fuel consumption continued to grow in absolute terms (Figure 1). Over the last ten years, the absolute consumption of energy from coal has remained fairly constant and its share in total energy consumption has dropped from 70 to 56 percent. Some of this decline was driven by an increased reliance on natural gas, which has a smaller carbon footprint. With growing demand for automobiles and air travel, crude oil consumption continues to rise.

Figure 1

How do we square China’s fairly constant consumption of energy from coal with stories of its continuing to build coal-fired power plants?

According to Xie Zhenhua, China’s Special Envoy for Climate Change, there is an ongoing process of upgrading in which modern, efficient plans are built and older ones are de-commissioned. Xie says that 120 gigawatts of coal-fired plants have been mothballed in recent years, which is more than most countries’ generating capacity. In 2021, China had 1300 gigawatts in coal-fired generating capacity.

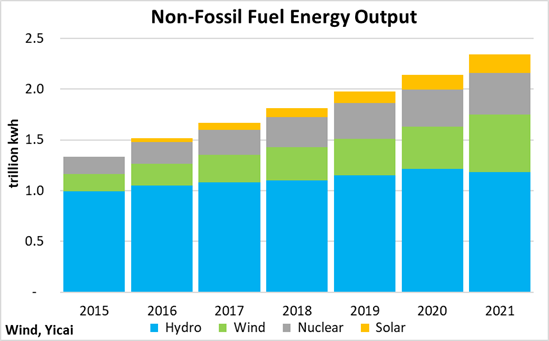

Just over half of China’s non-fossil energy production came from hydropower last year. Wind, nuclear and solar accounted for 24, 17 and 8 percent, respectively. The latter three have been the fastest-growing sources of non-fossil energy (Figure 2).

Figure 2

China’s energy transition is just getting started. For the country to become carbon neutral, it will have to accelerate. According to China’s long-term emission strategy, non-fossil fuels’ share in energy consumption will rise to 80 percent by 2060. This suggests a significantly faster pace of development than we have seen in recent years and implied in the 2025 and 2030 targets (Figure 3).

Figure 3

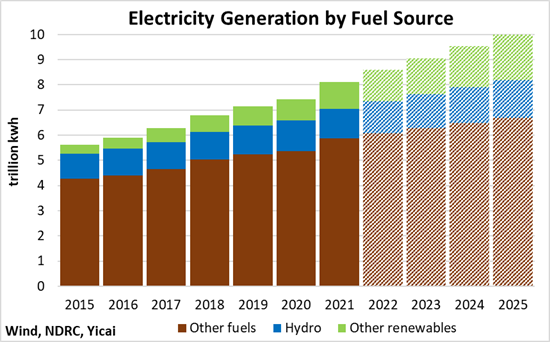

The Plan also sets targets on electricity generation by fuel source. By 2025, one-third of China’s electricity is to come from renewable sources, with hydro and other renewables accounting for 15 and 18 percent, respectively (Figure 4). While hydro’s generation share is essentially flat, that of other renewables is to climb by 7 percentage points between 2020 and 2025. Their share had grown by 5 percentage points during the previous five-year period.

Figure 4

China is counting heavily on wind and solar power to achieve its carbon reduction goals. It is planning to more than double the electricity-generating capacity from these sources between 2020 and 2030. This would bring China’s installed capacity of wind and solar to some 1,200 gigawatts.

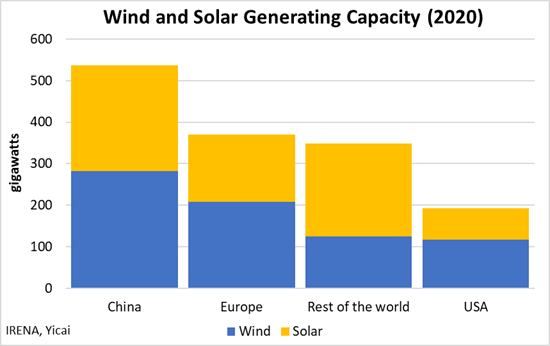

China is already the world leader in wind and solar. In 2020, its wind and solar generating capacity was almost three times as large as the US’s, 45 percent greater than Europe’s and 54 percent bigger than all other countries (Figure 5). China accounts for 37 percent of the world’s wind and solar generating capacity. With no other country planning as rapid an expansion, China’s share will continue to rise.

Figure 5

According to the Plan, annual renewable energy consumption will be equal to 1 billion tons of coal by 2025. This enhanced use of renewable energy would represent an annual savings of some 2.6 billion tons of carbon emissions. China’s carbon emissions were 10.7 billion tons in 2020.

China’s pivot from fossil fuels to renewables faces two major challenges.

The first challenge is getting the electricity to market at a reasonable cost. At the plant gate, the power generated by solar and wind is now competitive with coal. The problem is that renewables need wide open spaces, which tend to be far from the population centers in which the electricity is consumed.

The solution is to invest heavily in power transmission, both to connect the wind and sun farms to the grid and then to send the electricity across the country as efficiently as possible. The State Grid and the Southern Power Grid plan to invest CNY 2.9 trillion during the 14th Five-Year Plan period, 13 percent more than during 2016-2020.

A major part of this investment will be the doubling of China’s ultra-high voltage transmission capacity, to 105 gigawatts, over the five-year plan period. Ultra-high voltage transmission is 25 percent cheaper than lower voltage options. This is, in part, because ultra-high voltage lines only lose one-quarter as much power during the transmission process as lower voltage lines. China’s high-voltage transmission network is, by far, the world’s most extensive with 35 lines spanning 34,500 kilometers.

The second challenge renewables face is storage. Because wind and solar power depend on the weather, there can be a timing mismatch between power generation and electricity needs. Storage can help synchronize supply and demand.

The most common technique for storing power involves pumping water into a reservoir when the sun is shining or the wind is blowing. When the power is needed, the water runs out of the reservoir, turning turbines in the process.

In 2020, China had 30 gigawatts of this sort of pumped storage. Europe had 28, the US had 19 and the rest of the world had 43. According to China’s Five-Year Plan for Energy Development, pumped storage capacity is to reach 62 gigawatts by 2025, with another 60 gigawatts to be under construction. Pumped storage capacity operational in 2025 would represent about 7 percent of wind and solar generation, up from 5.6 percent in 2020.

China is also expanding battery-based storage. The State Grid plans to have 100 gigawatts of battery storage in place by 2030, up from only 3 gigawatts now. In addition, the authorities are encouraging the private sector to participate in the storage market by allowing them to buy and sell electricity.

As I finish writing this, it has begun to rain. It is really quite the downpour and it should help cool things off. I have turned off the air conditioner. The road to environmental sustainability will be a long one. And it will depend on restraining demand as much as on de-carbonizing supply.