The IMF’s Report on China’s Economy: Worth the Read Even if You Disagree

The IMF’s Report on China’s Economy: Worth the Read Even if You Disagree On February 3, the IMF released its on the Chinese economy. As a member of the IMF, China commits itself to an annual assessment of its economic and financial policies by the Fund’s staff. The staff’s findings are presented to the IMF’s Executive Board whose views are included along with the staff’s analysis.

The report belongs to the staff and its contents are not negotiated with the Chinese authorities. The authorities’ views are duly reflected in the report and a statement by Zhengxin Zhang, China’s Executive Director, is included in the package as well.

One may agree or disagree with the staff’s recommendations, but the publication of the report, which is available in as well as English, makes an important contribution to an informed discussion of China’s policies.

The report was based on conversations the staff had with Chinese officials through November 16 and it was completed on December 19, 2022. However, with the loosening of public health policies in December, China’s near-term outlook changed significantly. While the report does not reflect these changes, the IMF did incorporate them in its .

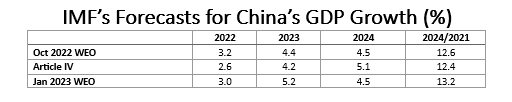

Table 1 presents the evolution of the Fund’s forecasts for China’s GDP growth in 2023 and 2024. The Fund expects December’s relaxation of public health policies to add a percentage point to growth this year. Growth between 2021 and 2024 is now expected to be 0.6 percentage points higher than in the Fund’s October 2022 WEO forecast.

Table 1

Most of the staff’s policy advice remains relevant despite these changes. Foremost among these is the recommendation for a large-scale restructuring of the real estate sector.

The staff note that the authorities have undertaken wide-ranging measures to boost homebuyer demand and have provided funding to complete housing that was paid for but which remains unfinished.

However, the staff are concerned that, despite these measures, potential homebuyers remain wary about purchasing apartments. In addition, they feel that the amount of public funds offered is too small relative to the stock of unfinished housing.

The staff use three methods to estimate the cost of completing unfinished, pre-sold housing. Their estimates suggest that the cost is large, ranging between 3 and 8 percent of GDP. Given the lack of information on the distribution of troubled projects, their degree of completion and the availability of escrowed cash, there are wide bands of uncertainty around the staff’s point estimates.

The staff recommend three measures to restore homebuyer confidence. First, the government should undertake a proactive restructuring of the troubled developers to protect individuals, who have already made purchases, against losses. Second, it should institute an insurance scheme, underwritten by financial institutions and paid for by developers, that would protect future homebuyers. Third, it should reform the legal framework for pre-sales to prevent moral hazard.

The staff are bearish on China’s medium-term prospects. They believe that China’s potential GDP growth has fallen from 10 percent in the mid-2000s to only 4.7 percent in 2021. Although some of this decline has come from a smaller labour input, the staff say that most of it is due to a slower rate of total productivity growth.

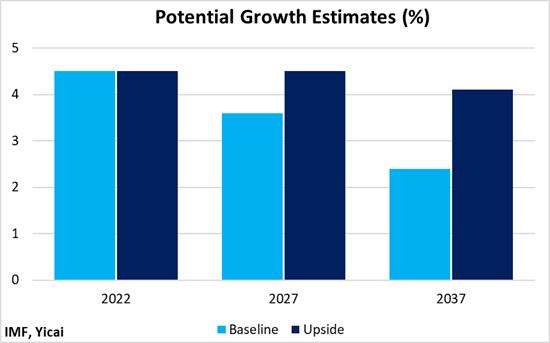

In the papers that accompany the Staff Report, the staff conduct a detailed projection of China’s potential growth over the next 15 years. According to their baseline estimate, China’s potential growth will continue to fall, reaching 2.4 percent in 2037. However, the staff believe that the implementation of a package of growth-enhancing reforms could slow the decline (Figure 1). Under this upside scenario, these reforms have the potential to lift the level of real GDP by some 18 percent above baseline by 2037.

Figure 1

The staff point to five areas in which growth-enhancing reforms could be undertaken.

First, the productivity gap between state-owned and private enterprises should be closed. Reducing state-owned enterprises’ leverage and allowing more efficient private firms better access to finance can significantly raise the productivity of the manufacturing sector.

Second, the manufacturing sector’s productivity can also benefit from reforms that facilitate the entry and exit of firms.

Third, increasing social spending can reduce excess savings and promote consumption (and investment) in the service sector, thereby boosting its productivity.

Fourth, the retirement age should be gradually increased from 60 for males and 55 for females to 65.

Finally, improving the quality of education and enhancing access to schooling will raise the level of human capital.

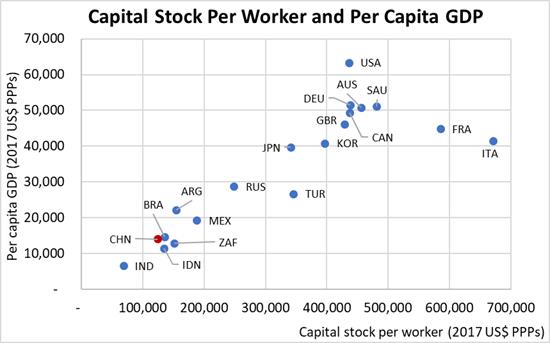

While it is hard to argue with growth-enhancing reforms, I do want to take issue with the way the Fund staff characterize China’s “investment-led growth strategy” which they call “excessive” and “unsustainable”. It is true that the ratio of investment to GDP is very high in China. But the picture changes if we look at its capital stock per worker.

Figure 2 plots the capital stock per worker against GDP per capita for the G20 countries. China’s capital stock per worker is just about where we expect given its per capita GDP. Seen from this perspective, China’s high investment rate is part of a stock-adjustment process. It can take many years to build a country’s capital stock. China’s high rate of investment stems from both the very rapid increase in its labour force and the small and outdated capital stock with which it began its development process.

Figure 2

The staff rightly note that China’s investment has become “increasingly less productive” over time. Nevertheless, it appears that the productivity of China’s investments remains relatively high.

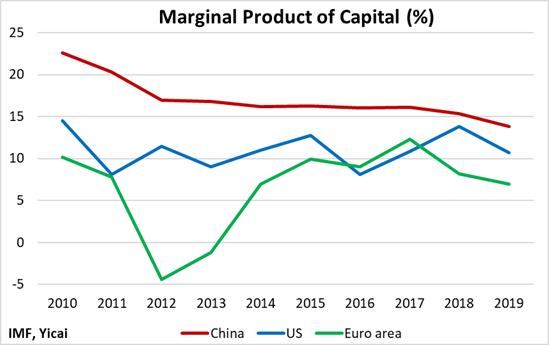

One measure of investment’s productivity is the marginal product of capital (the inverse of the ). The marginal product of capital – the incremental amount of GDP we squeeze out from the last addition to the capital stock – can be calculated as GDP growth divided by the investment-GDP ratio.

It is best to look at the marginal product of capital over the business cycle because the volatility of GDP growth can give odd results. Figure 3 shows that the marginal product of capital in China fell from 23 percent in 2010 to 14 percent in 2019. Still, despite China’s investment rate being nearly twice as high as those in the euro area and the US, its marginal product of capital was double that of the euro area’s and almost 30 percent higher than the US’s.

Figure 3

The staff also take exception to China’s supply-side response to supporting the economy in the aftermath of the Covid shock. While most other economies implemented demand-side policies that provided support to households, China used credit policy to steer funding to small- and medium-sized enterprises and it increased infrastructure spending.

The staff take China to task for not relying more on reducing interest rates. However, since the Covid shock reduced aggregate supply as well as aggregate demand, China’s more muted monetary response may have been appropriate.

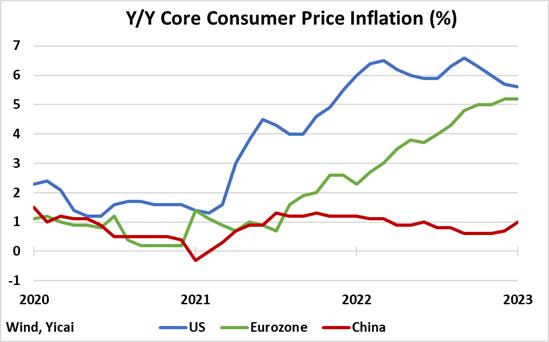

Over the last three years, the cumulative output loss in China, the US and the Eurozone relative to trend was quite similar. In other words, the three economies faced broadly similar output gaps, on average, over 2020-2022. While the Fed and the ECB aggressively cut interest rates, China’s response was more targeted. Although there are many factors at play, these differing monetary policy responses help explain why core inflation in China remained relatively stable (Figure 4).

Figure 4

The staff characterize China’s infrastructure spending as “low return” and “increasingly less effective”. However, considering that infrastructure spending typically provides public goods, I think assessing its effectiveness is difficult.

Last year, investment in electricity production was up 24 percent year-over-year. are being made to develop solar and wind power in the Gobi and other desert areas, while spending on ultra-high voltage transmission is also on the rise. Investment in water management and conservation was up 14 percent. Many are underway some of which transfer water to arid areas to support agriculture and others help control flooding. Investment in information transmission was up 22 percent last year, as spending on data centers increased.

Many workers had to be hired to undertake these investments. Given the slack in the economy last year – in particular, the weakness in the employment-intensive real estate sector – it is hard to imagine that China’s additional infrastructure spending squeezed out other investments. To me, China’s preference for paying workers to build infrastructure, even if it is not fully utilized in the short run, seems like a better use of public resources than simply transferring the funds to households.

I do not have to agree with the Fund staff to appreciate the depth of analysis that goes into their report. I hope their hard work gets the attention it deserves and that it spurs further debate on these key economic issues.