What Kind of Trade Deal Can the US and China Cut?

What Kind of Trade Deal Can the US and China Cut?(Yicai) Sept. 13 -- No one wins a trade war.

Not only did the sky-high tariffs the US and China imposed on each other in April threaten to undermine growth in the world’s two largest economies, they also would have inflicted serious collateral damage on the rest of the world.

That is why we all heaved a huge sigh of relief on May 12, when American and Chinese officials agreed to massive reductions in their reciprocal tariffs for 90 days. In a promising development, they also agreed to establish a mechanism for ongoing trade discussions.

In June, Presidents Trump and Xi had an hour-and-a-half-long phone call. Apparently, the tenor of the call was constructive. Senior officials from both sides held the first meeting of the China-US economic and trade consultation mechanism in London later that month. They followed up with meetings in Stockholm in July. In mid-August, both sides agreed to extend their tariff truce until November 10.

Negotiations are continuing and we are hoping for an agreement that will reduce tensions between the two giants and allow the rest of the world to breathe easier.

To think about what sort of deal may be reached, it is useful to step back and look at the wider economic context.

President Trump is fixated on trade imbalances.

He believes that the US goods deficit, which reached $1.2 trillion in 2024, is the result of its trading partners’ bad behaviour. Indeed, the “reciprocal tariffs” he imposed in April, under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, appear to have been calculated as a function of the size of the bilateral goods deficits.

In 2018, President Trump imposed a series of tariffs to address the US’s trade imbalance with China. At that time, the bilateral deficit was some $400 billion or close to half of the US’s overall goods deficit. During the first Trump Administration, the US average trade-weighted tariff on Chinese goods rose from just over 3 percent to 21 percent. China responded to the Trump Administration’s tariffs with those of its own, which rose from 8 to 22 percent. The tariffs remained in this range until early in President Trump’s second term.

From China’s perspective, these tariffs have been costly. Moreover, their cost has grown over time as US importers became able to find substitutes for Chinese goods.

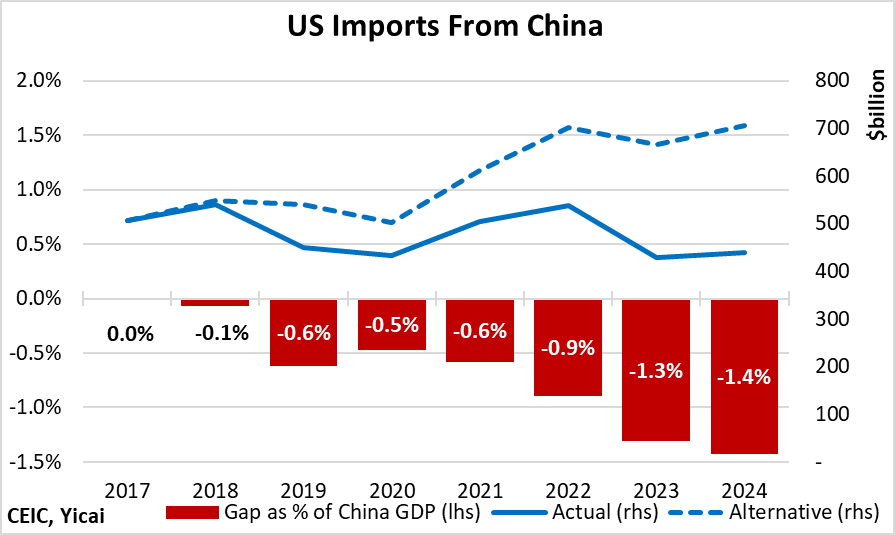

China’s share of US imports fell from 21.5 percent in 2017 to 13.5 percent in 2024. To estimate the impact the tariffs had on the Chinese economy, we can construct an alternative scenario in which China’s share of US imports remained at its 2017 level. We can then compare the US’s actual imports from China against the constant-import-share alternative scenario (Figure 1). In 2024, the difference was $267 billion or 1.4 percent of China’s GDP. However, since China’s exports typically contain imported components, the loss on a value-added basis would be some 20-25 percent smaller.

Figure 1

Chinese importers were not the only ones hurt by the tariffs imposed during the first Trump Administration.

Amiti and coauthors find that the (Section 232 and Section 301) tariffs imposed in 2018 cost US consumers $3.2 billion per month in taxes and an additional $1.4 billion per month in deadweight losses. This would be equivalent to an annual cost of close to $170 for every American man, woman and child. Moreover, by protecting them from competition, the tariffs also incentivized US firms to charge higher prices than otherwise, further reducing consumer welfare.

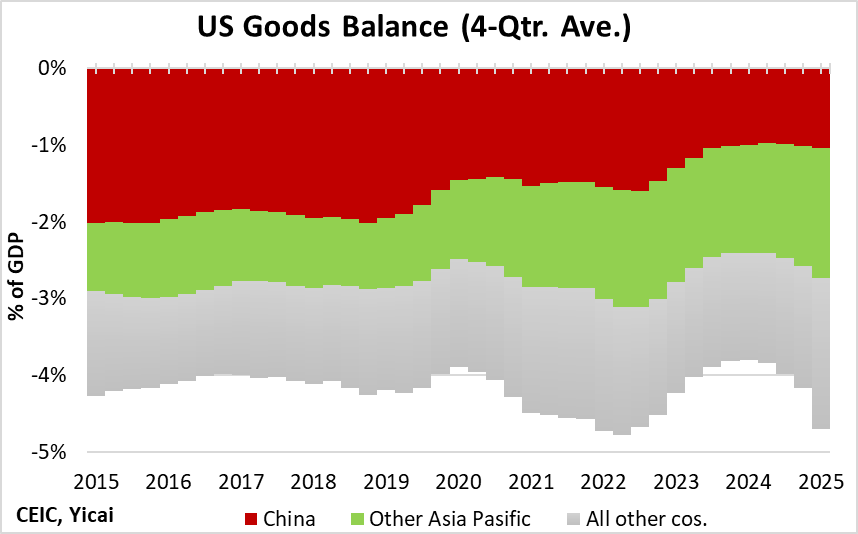

The tariffs had their desired effect on the US’s trade deficit with China. By 2024, it had fallen to 1 percent of US GDP from 2 percent in 2018. However, the tariffs did nothing to address the US’s overall trade deficit, which has remained at some 4 percent of GDP over the last decade (Figure 2).

Figure 2

In his second term, President Trump has doubled down on tariffs as a trade policy tool, raising them to levels not seen since the late 1930s. This time, however, the tariffs are being imposed on all of the US’s trading partners.

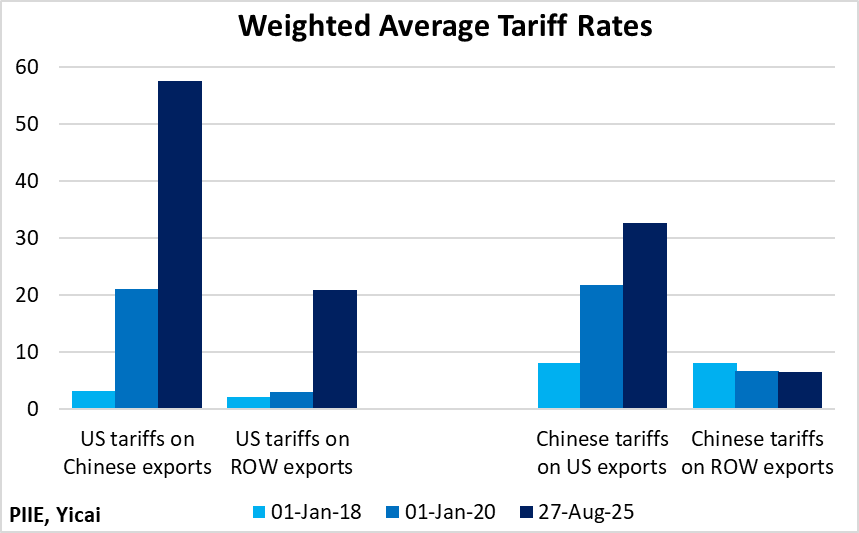

Currently, the US’s trade-weighted tariff on China is almost 60 percent, close to three times as high as during the first Trump Administration (Figure 3). Moreover, its average trade-weighted tariff on all other countries jumped from 3 to 21 percent over the same period.

For its part, China increased its average tariff on the US from 22 to 33 percent while maintaining those on the rest of the world at 6.5 percent, 1.5 percentage points lower than pre-trade war levels.

Figure 3

The tariffs imposed in April will be even more painful than those in 2018. Chinese exports to the US between May and August were down 12 percent year-over-year, while its sales to all other countries were up 9 percent in the same period.

The reciprocal tariffs will also be costly for US consumers. The Budget Lab at Yale University estimates that those currently in place will cost US households an average of $2,300. It sees US GDP growth slowing by half a percentage point in both 2025 and 2026. In the long run, US GDP is projected to be permanently 0.4 percent below the pre-tariff baseline.

Clearly, the trade war is a lose-lose proposition, hurting both the US and its trading partners. What, then, are the prospects for a deal between China and the US that will improve outcomes for everyone?

President Trump has shown a willingness to cut deals with the US’s trading partners that offer tariff reductions in return for some combination of increased purchases of American goods, enhanced market access and commitments to invest in the US. As the state of his economy deteriorates, I believe that President Trump will become increasingly eager to make such a deal with China.

President Trump’s reciprocal tariffs are designed to boost the US economy. However, in the near term, the tariffs suck purchasing power out of US consumers. This is why most forecasters believe that they will have a negative impact on the US economy, even in the long run.

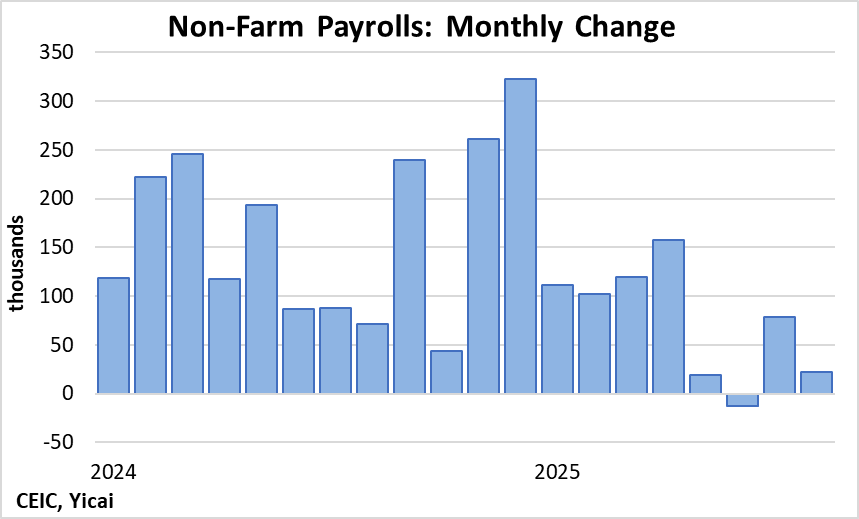

Recent readings from the US labour market show that employment growth has fallen dramatically since the tariffs were imposed. Between May and August, the average monthly growth in non-farm payrolls was only 27,000 (Figure 4). This is down from 156,000 between January 2024 and April 2025 (these data are subject to revision). The 22,000 increase in August was well below expectations of 75,000.

Figure 4

So, how can China help support the US economy as a way to reach a deal with President Trump?

One option is to agree to buy billions of dollars of US goods, as it did in 2020. That deal was undermined by the outbreak of Covid, which led to a collapse in global trade. Such a deal has a better chance of success this time.

A second option is to increase the effectiveness of US monetary policy. Given the weakness in the US labour market, the Fed is likely to begin cutting interest rates this month. In addition to lower borrowing costs for firms and households, lower interest rates will weaken the US dollar, potentially boosting US net exports.

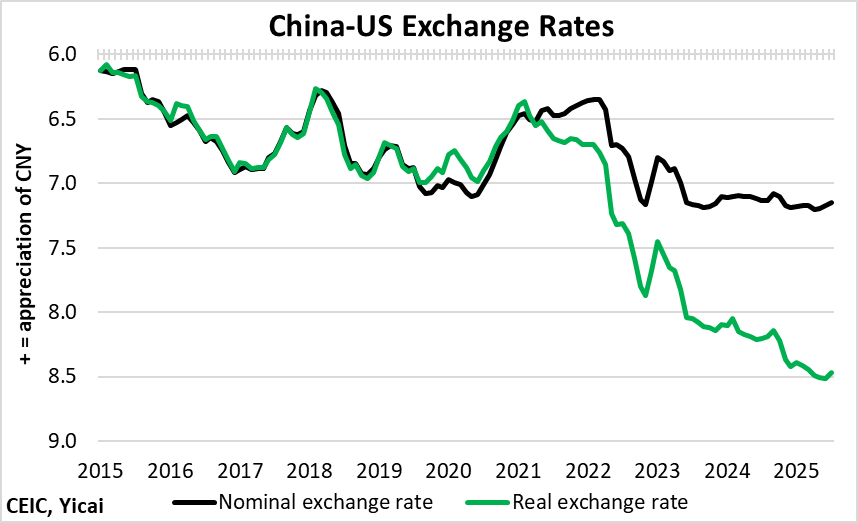

While the renminbi has been tightly managed against the US dollar, the Chinese authorities could offer to allow their currency to appreciate modestly. Due to much better inflation control in China than in the US, the renminbi is already super-competitive. Between January 2020 and July 2025, the US price level rose by 24 percent, but Chinese prices were only up 2 percent over the same period. Moreover, the renminbi depreciated by 2.5 percent against the dollar. That means that the real renminbi – the nominal exchange rate adjusted for relative prices – has actually fallen by 20 percent (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Apart from being an attractive bargaining chip for a deal with the US, appreciating the renminbi would be helpful for China to rebalance demand from external to domestic sources. A stronger currency makes imports cheaper and increases domestic purchasing power.

A modestly stronger exchange rate would have a dampening effect on China’s exports, but the real renminbi is already very cheap. This, in part, is why China’s exports to all countries outside of the US have been doing so well. Moreover, an agreement to roll back the Trump Administration’s tariffs would offset much of the effect of the appreciation in the US market.

The final element of a deal could be the further relaxation of US restrictions on the export of chips and chip-making equipment. President Trump already appears to be moving in this direction. In return for a 15 percent cut of their sales, he is allowing Nvidia and AMD to sell China powerful chips that had previously been banned. Earlier this year, he allowed the world’s three leading semiconductor design software companies — Synopsys, Cadence Design Systems and Siemens – to sell their products in China without having to apply for licences. President Trump does not seem as bothered by the national security concerns that preoccupied the Biden Administration.

So, a potential deal could look like this: both countries roll back their tariffs; China supports the US economy through some combination of goods purchases and a modest nominal appreciation; and the US relaxes its controls on the export of advanced chips and chip-making equipment.

The devil, as they say, will be in the details, but a deal along these broad lines would certainly be helpful for the US, China and the rest of the world.