GDP Slows Sharply in Q3

GDP Slows Sharply in Q3(Yicai Global) Oct. 24 -- On October 18, China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) released its National Accounts for the third quarter. The data showed a sharp slowing in economic activity with GDP decelerating to 4.9 percent from 7.9 percent in 2021 Q2. While the weakness was widespread, manufacturing and real estate made the biggest contributions to the reduced year-over-year growth. The outturn was weaker than the 5.4 percent expected by the economists by the Yicai Research Institute.

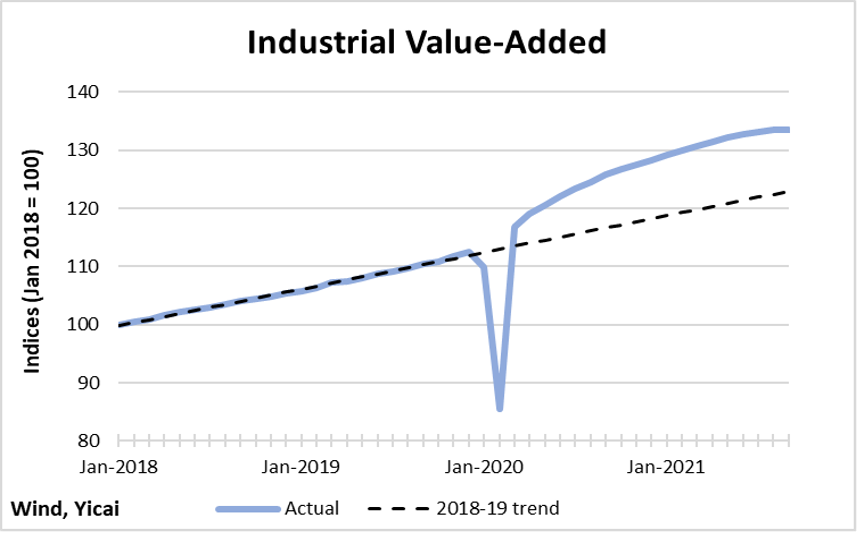

To a certain extent, the manufacturing sector is a victim of its own success. Industrial value-added has had an exceptional run since its recovery from the pandemic-induced drop in February 2020. By September 2021, industrial value-added was 9 percent above its pre-pandemic trend (Figure 1). This means that we wouldn’t have expected China’s industrial sector to produce this much for another year and a half. China’s industrial sector has benefitted from very strong export demand. Exports were up 24 percent, year-over-year, in the quarter.

Figure 1

The problem is that the economy has not been able to produce inputs fast enough to support this pace of industrial production. Earlier this year, the focus was on a shortage of computer chips. While that bottleneck still constrains output in autos and other sectors, attention has recently turned to coal.

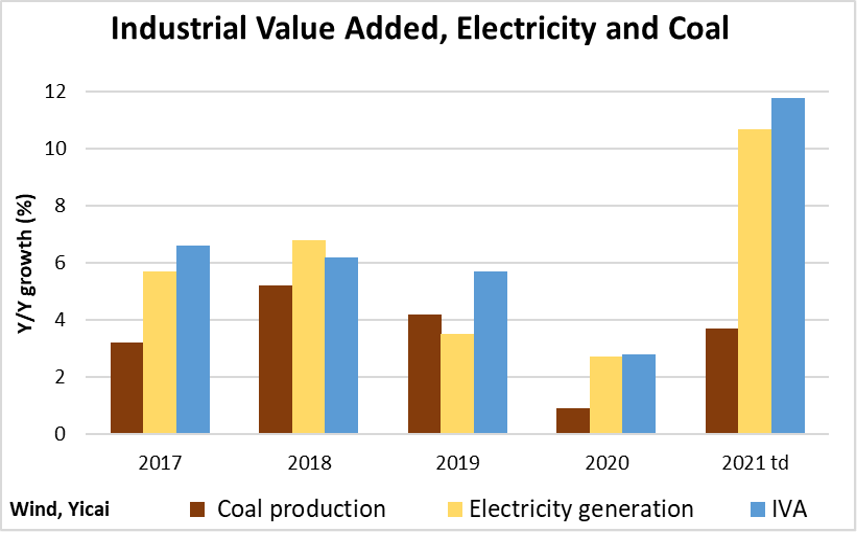

Coal-fired power plants supply close to two-thirds of China’s energy needs. Investment in coal mining has not kept pace with the tremendous growth in industrial output, in part, because China is in the process of transitioning to a low-carbon economy. The mismatch between the demand for and the supply of coal reached a head this year, with industrial value-added up close to 12 percent, year-to-date, while coal production was up by less than 4 percent (Figure 2).

Figure 2

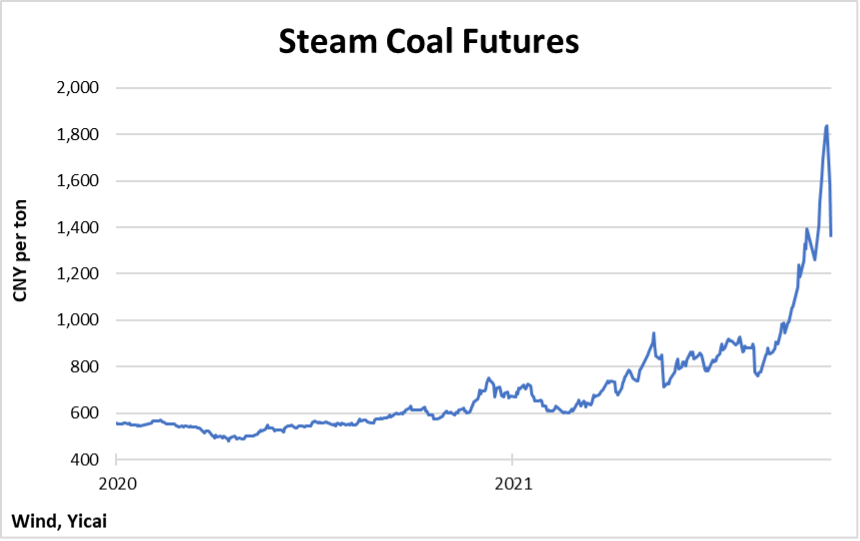

As a result, the coal price, which has typically been quite stable, tripled since the beginning of the year. According to NBS spokesman , the State Council is taking steps to boost energy supply and ensure price stability. Coal import volumes were up almost 40 percent year-over-year in the quarter. Nevertheless, they remain about 5 percent below the volumes imported in the third quarter of 2019. Moreover, imports typically account for 10 percent of China’s coal supply, so it is not clear how much of an offset they can provide in the near term. Reuters that 153 domestic coal mines received approvals to expand capacity. These mines are expected to add 55 million tons of additional coal supply in the fourth quarter, or about 5 more days’ worth at September’s rate of production. In an effort to curb demand, utilities are being allowed to raise electricity tariffs. In the manufacturing heartland of Guangdong, the price of electricity at peak times is up .

On October 19, the National Development and Reform Commission – China’s economic super-ministry – said it would take to bring coal prices into a reasonable range. As a result, the coal price fell on each of the following three days and ended the week 25 percent off of its peak (Figure 3).

Figure 3

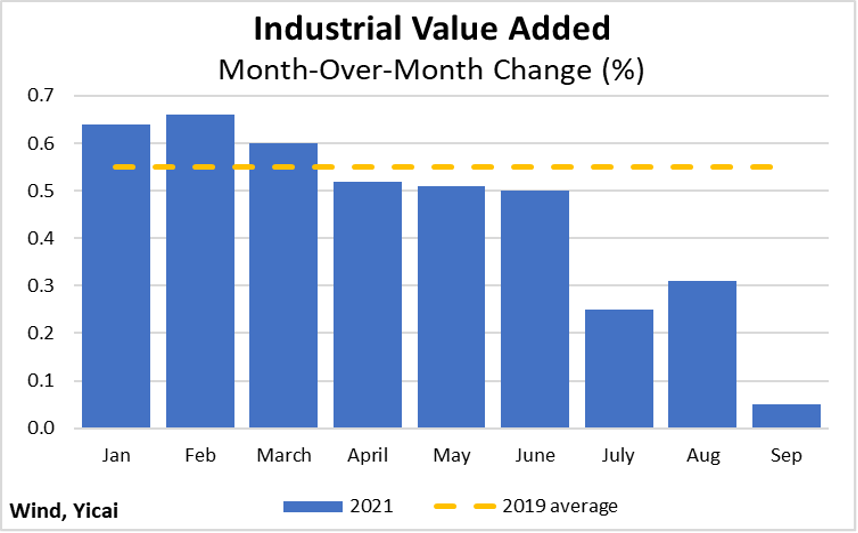

To ensure adequate coal supplies, local governments have been forced to resort to power rationing in the majority of China’s provinces. A lack of power is part of the reason why industrial value-added only increased by 0.05 percent, month-over-month, in September (Figure 4). Many analysts expect that the imbalance in the power market will be resolved by year-end and it is encouraging that electricity production grew by 4.9 percent in September, up from 0.9 percent in August. However, the rising price of coal suggests that supply is far from sufficient. This poses a risk that power shortages could continue to impact growth in the fourth quarter.

Figure 4

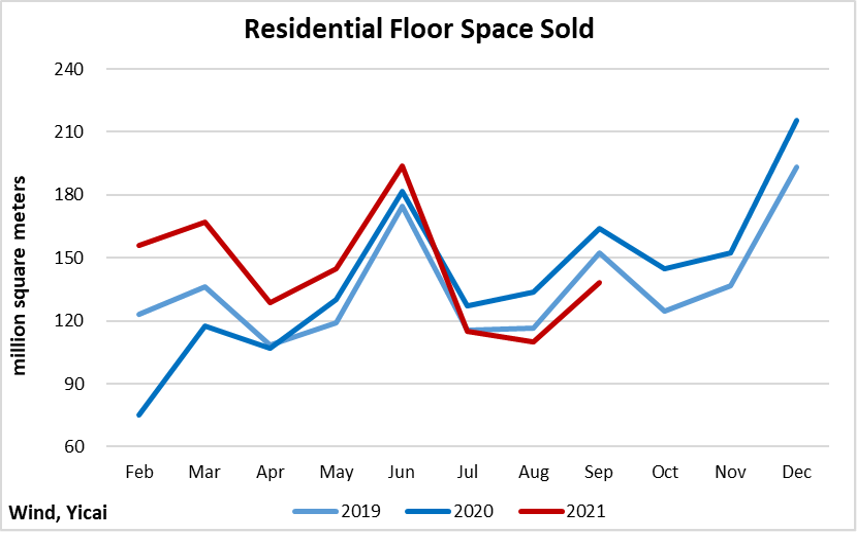

The third quarter marked a turning point in the Chinese real estate market. In the first half of 2021, sales of residential floor space were well above levels seen in the last two years (Figure 5). Since July, buyers seem to have lost their appetite for housing. This is partially due to their having gorged themselves earlier on: notwithstanding the weakness in Q3, year-to-date sales are still more than 10 percent higher than in the two previous years.

Homebuyers could also be on the sidelines because of a cyclical decline in prices. Apartment prices edged down in September, their first monthly decline in six years. China’s property developers are trying to generate the cash flow needed to comply with the government’s “Three Red Lines” – a policy designed to rein in their financial risks. The developers have been discounting the prices of their new apartments to boost sales and reduce their leverage. In some cases, to limit such discounting in order to maintain orderly market expectations.

Figure 5

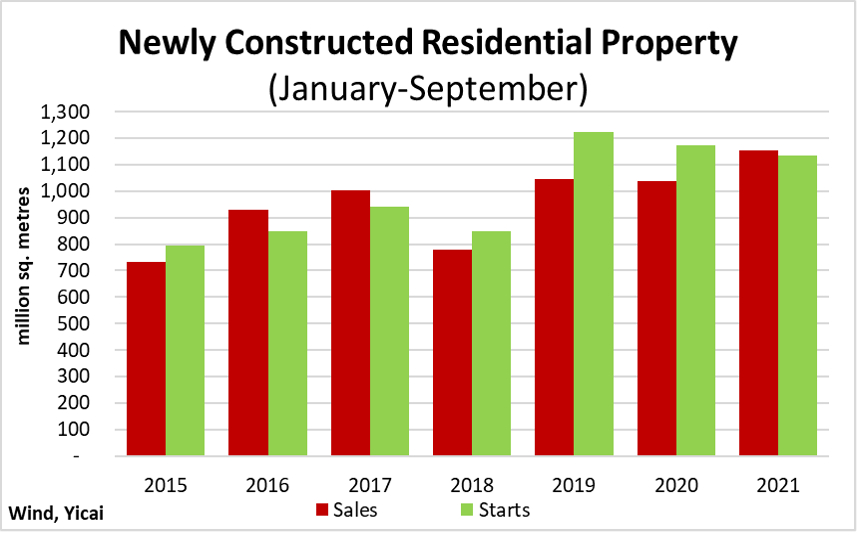

Developers’ deleveraging is also having an effect on real estate supply. Housing starts are down 3.3 percent year-to-date (Figure 6). To some extent, this represents a correction of modest over-supply in previous years. Nevertheless, if supply continues to lag demand, prices could begin to rise more rapidly and we could see those buyers, who are currently sitting on the sidelines, re-enter the market.

Figure 6

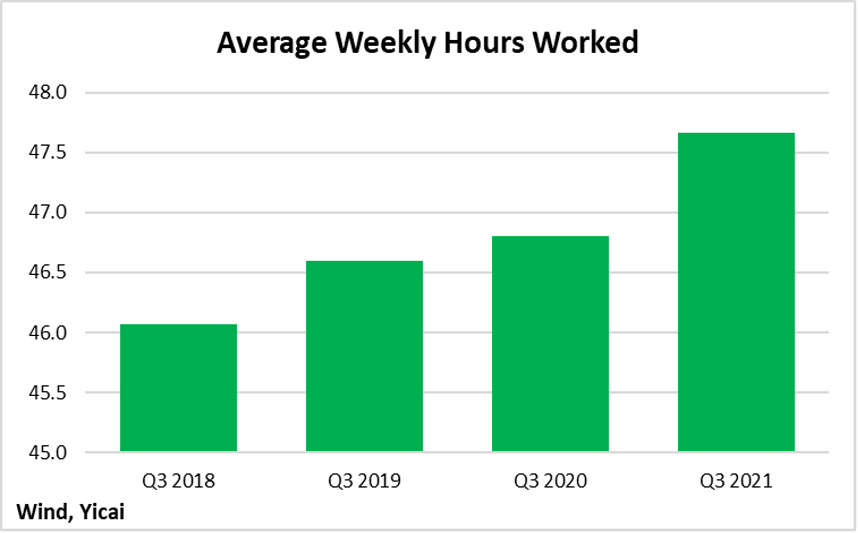

The labour market continues to improve. The headline and youth unemployment rates both declined. A total of 10.45 million formal new jobs have been created in Chinese cities so far this year, or 95 percent of the amount targeted by the government. While the pace of new job creation appears to have slowed a bit, the demand for labour is still strong. On average, workers put in 54 more minutes per week in the third quarter than they did a year ago (Figure 7).

Figure 7

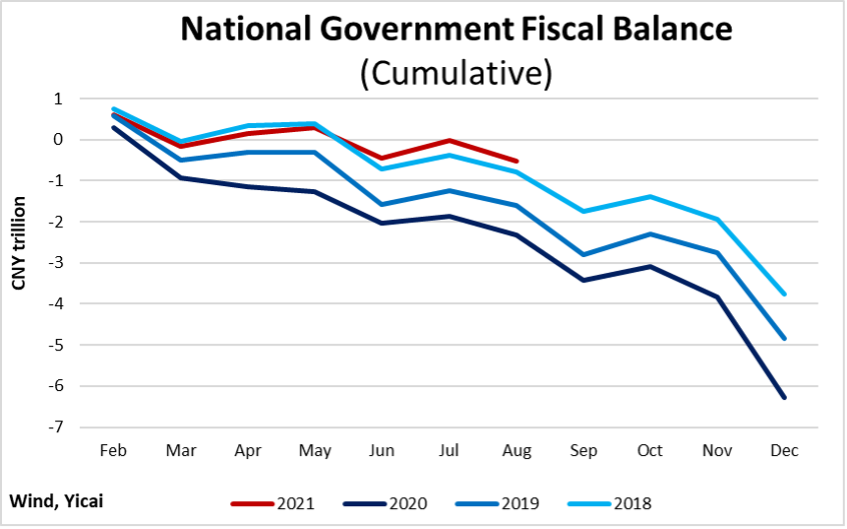

While the ongoing deceleration of the economy in Q3 has been sharper than anticipated, we see no sign that policymakers are ready to use their macroeconomic tools to support the economy. In fact, fiscal policy appears to be a significant headwind. As a result of very strong revenue growth this year, the cumulative fiscal deficit to August was CNY500 billion, compared to CNY2.3 trillion in 2020 (Figure 8). A smaller deficit means that the government is putting less money into the economy than it did last year. At annual rates, this “negative fiscal impulse” represents a drag of 2.6 percent of GDP.

The government’s 2021 budget document plans for a fiscal deficit that is broadly similar to last year’s. The government typically does not miss its budget targets by much. This suggests that fiscal policy could turn more accommodative in the fourth quarter. However, with the economy suffering from various supply constraints, fiscal stimulus would need to be applied judiciously to not make a bad situation even worse.

Figure 8

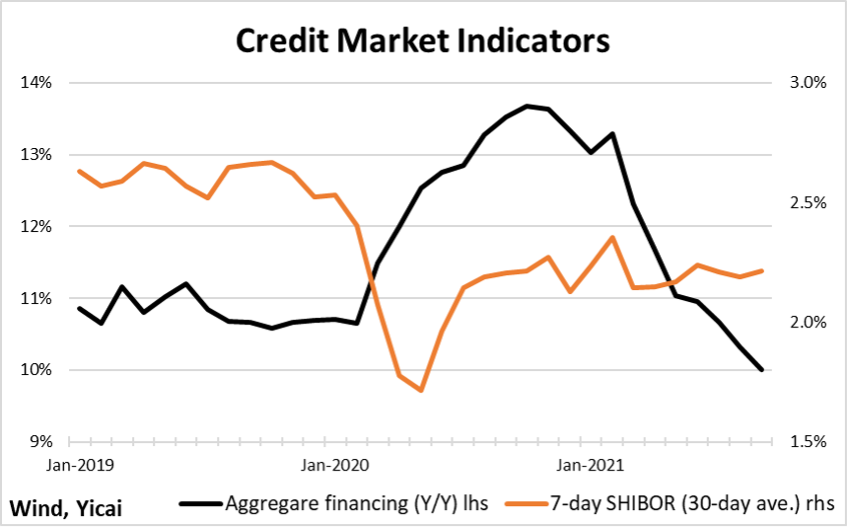

Monetary policy has engineered a tremendous credit tightening. The growth of aggregate financing to the real economy slowed from 13.7 percent in October 2020 to 10 percent in September (Figure 9). This is even somewhat slower than its pre-pandemic rate. Despite this slowing in credit, interest rates remain stable. This is likely because the economy is still digesting last year’s credit boom and suggests that credit demand is slowing in step with credit supply. Recent from the People’s Bank of China indicate that a loosening of monetary policy is unlikely in the fourth quarter. As a result, the market is revising its expectations of a cut in the Required Reserve Ratio.

Figure 9

There are four reasons that macroeconomic policy is unlikely to be more supportive in the face of the sharp GDP slowdown. First, the economy will probably grow by 8 percent for the year as a whole and comfortably exceed the government’s 6 percent target. Second, the labour market remains stable, with wages growing at a reasonable rate. Third, the difficulties faced by the property developers show how important it is to rein in financial risks. Fourth, there is little that macroeconomic policy can do to relieve the supply bottlenecks that are impinging on output.

Nevertheless, policymakers will not stand idly by. They are likely to continue to use their microeconomic levers to increase the supply of coal and computer chips. At a symposium held at the National Development and Reform Commission last week, Vice Premier Han Zheng emphasized the need to ensure in the coming winter and spring. Similarly, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology recently said that it expected the chip in the fourth quarter.