What’s Next for US-China Trade?

What’s Next for US-China Trade? (Yicai Global) Feb. 25 -- On January 15, 2020, China and the US signed the so-called . The Agreement sought to improve the protection of intellectual property rights, ensure that the transfer of technology is voluntary, promote trade in agricultural products, liberalize market access for financial services and refrain from competitive devaluations. But the headline-making section of the Agreement was the one that committed China to increase its purchases of American goods and services.

Even under the best of conditions, China’s compliance with the Agreement’s purchase targets would have been a Herculean task.

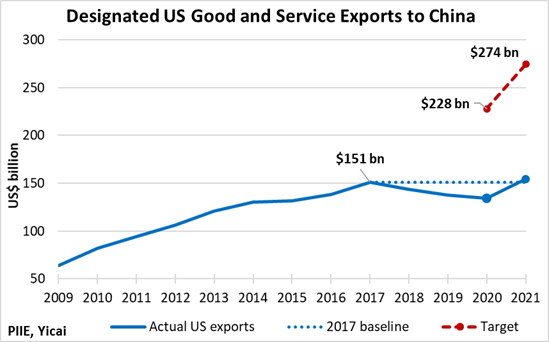

The Agreement covered close to 80 percent of the US’s goods and services exports to China. Between 2009 and 2017, these designated US exports grew by USD87 billion, or by USD11 billion, on average, per year. Under the Agreement, they were to grow by a cumulative USD200 billion over 2020-21 from their 2017 baseline. This works out to USD100 billion per year, on average, or nine times faster than they had grown historically. To make matters worse, the designated exports had fallen between 2017 and 2019 due to the trade war, putting the targets further out of reach (Figure 1).

Figure 1

From the outset, analysts saw the export targets embedded in the Agreement as . Attaining them would have required a massive amount of “trade diversion” – China would have needed to cut back sharply on imports from its other trading partners to make room for its purchases from the US.

For example, in agriculture, where the trade is mostly in commodities rather than processed goods, by the US Department of Agriculture and the University of California at Davis showed hitting the targets would have resulted in large losses for Australian, Canadian and Brazilian exporters. Trade policy based on “robbing Peter to pay Paul” would have been bound to cause frictions between China and its trading partners.

While the Chinese government is certainly powerful, it is unclear that it had the tools to affect a dramatic shift in imports. Foreign firms purchase about 40 percent of China’s imports. Their supply chains link back to their home countries. Another one-third of China’s imports is purchased by private Chinese firms whose supply relationships reflect their search for the best product at the lowest price. Undermining these relationships would have resulted in shoddier or more expensive Chinese products. The remaining quarter of Chinese imports is purchased by state-owned firms. Here the government had more leverage. But these firms typically purchase upstream products like crude oil, ores and grains. They would have hardly been in a position to buy the diversified basket of manufactured goods and services designated under the Agreement.

A second problem with the targets came from the American side. Analysts that the US economy had enough spare capacity to service China’s additional export demand. In late 2019, the US economy did not appear to have a lot of slack. Indeed, the unemployment rate was at a 50-year low and small- and medium-sized businesses were complaining about how difficult it was to find qualified workers. Thus, hitting the export targets would have required a substantial diversion of the US’s domestic resources.

A careful of the data by Chad Brown at the Peterson Institute for International Economics explains why US exports fell well short of the targets. Not only were the targets unrealistic to begin with, but unforeseen events – most notably the pandemic – resulted in actual exports over 2020-21 only reaching 57 percent of their targeted amount.

Brown notes that manufactured goods made up the most significant part of the deal (Figure 2). But with the bilateral tariffs on autos and auto parts largely in place, the US’s vehicle exports dropped sharply. In addition, companies like Tesla and BMW moved production designated for China out of the US to mitigate the costs imposed by the tariffs. Moreover, Brown points out that Boeing shut its production down following the crashes of two of its 737 MAX planes. As a result, aircraft and aircraft part sales only reached 18 percent of their target.

Travel is, by far, the largest component of US service exports to China. With the outbreak of the pandemic, travel – for tourism, education and business purposes – ground to a halt.

Agriculture was the best-performing component of US exports to China, with sales reaching 83 percent of their target. However, this outcome was costly. Brown notes that President Trump paid farmers “tens of billions of dollars” in subsidies to offset the effects of China’s tariffs.

Finally, energy exports only hit 37 percent of their target. Brown attributed this, in part, to capacity constraints in the US energy industry. Industry leaders President Trump that achieving the targets would strain production capacity and shipping infrastructure. In fact, the additional amounts that China was supposed to purchase exceeded the US’s incremental production, indicating just how unrealistic the targets were.

Figure 2

How should the US respond to the glaring shortfall between the Agreement’s targets and actual exports?

It is hard to expect China to have complied with import targets that were effectively unattainable. Indeed, some analysts suggested that the Agreement’s targets were essentially “theatre” and intended to help with Trump’s in 2020 rather than the result of a carefully considered trade policy.

Luckily, the pandemic offers the Biden Administration a face-saving response. It can be characterized as an “act of God” which prevented the targets from being reached. In addition, the Biden Administration can point to the many areas of the Agreement with which China complied as “wins”.

Not only did China refrain from a competitive devaluation, the renminbi appreciated by 10 percent against the US dollar between December 2019 and December 2021.

While US exports of agricultural products failed to meet their target, they were 62 percent higher in 2021 than they had been in 2017, indicating that China did, indeed, facilitate agricultural trade.

China also liberalized market access for foreign providers of financial services. It allowed foreigners to their ownership stakes in and firms from 51 to 100 percent.

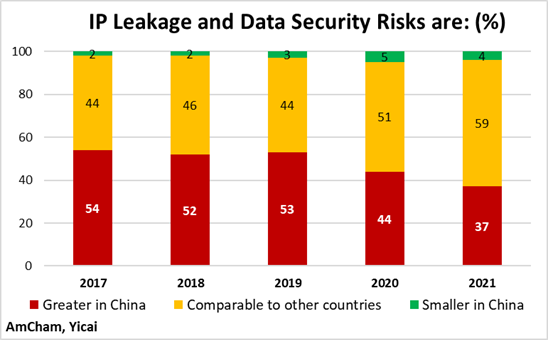

China is making progress in protecting foreign companies’ intellectual property. According to surveys conducted by the American Chamber of Commerce in the People’s Republic of China (AmCham), US firms see intellectual property leakage and data security risks in China becoming more and more comparable with what they experience in other countries. In the latest survey, just over one-third of the respondents felt that the risks were greater in China than elsewhere. This is down from more than half as recently as 2017 (Figure 3). Survey respondents indicated that intellectual property protection is one of the key areas in which China’s Foreign Investment Law, which took effect on January 1, 2020, is having a positive impact.

Figure 3

China is also making progress in reducing forced technology transfers. In its most recent survey, only 3 percent of AmCham’s respondents reported having shared their technology because of informal pressure from the authorities. This was down from 11 percent in the previous year’s survey.

Overall, fewer and fewer US firms operating in China see themselves as being treated unfavourably. This argues for the Biden Administration’s setting aside the Trump-era rhetoric, scaling back its tariffs and working cooperatively with its Chinese counterparts toward resolving remaining frictions.