November Data: The Bright Spots Dim

November Data: The Bright Spots Dim(Yicai Global) Dec. 19 -- On December 15, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) released its for November. Given the spike in infections, it comes as no surprise that the economy weakened significantly, continuing the negative trend we saw in October.

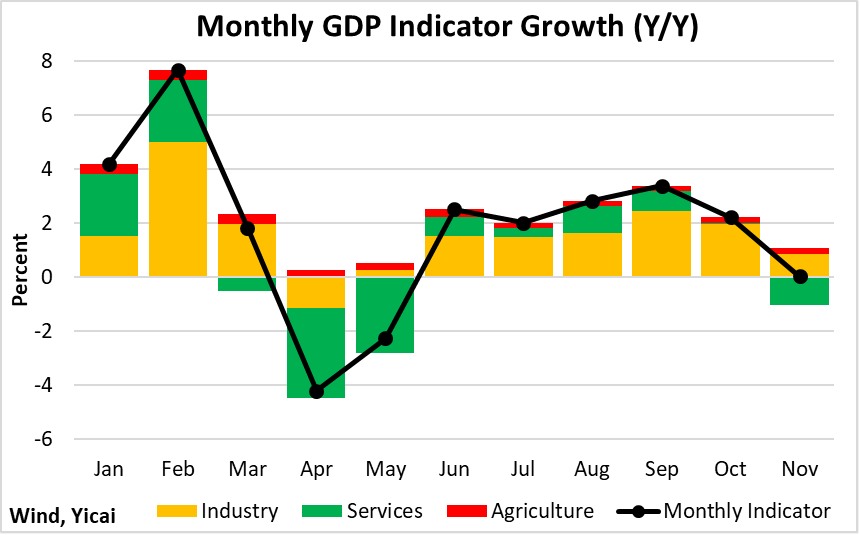

To get as broad a view as possible of how the economy is evolving, I rely on our monthly GDP indicator, which is a weighted average of the NBS’s industrial value added and service production indices as well as an estimate for the agricultural sector. This indicator suggests that economic growth essentially ground to a halt in November following 2.2 percent growth in October (Figure 1).

Figure 1

The slowdown in November was broad based and many of the economic bright spots we observed in previous months have dimmed. Industrial value added slowed from 5.0 percent in October to 2.2 percent. At the same time, the service sector declined by close to 2 percent following no growth the previous month.

For much of the last three years, strong exports had been a bright spot.

The relative resilience of Chinese supply chains helped offset the pandemic-induced weakness in domestic demand. Unfortunately for China, its trading partners are having problems of their own. Foreign demand is slowing as central banks around the world tighten monetary policy to bring down inflation.

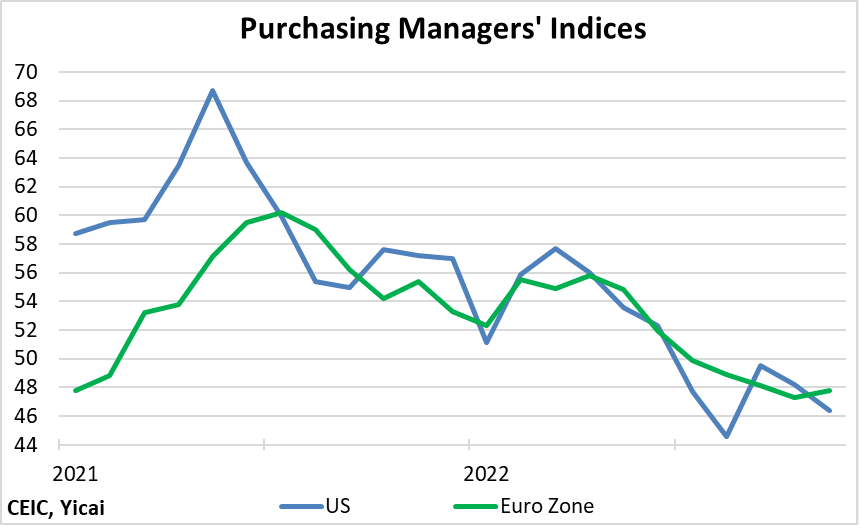

The extent of the slowdown in Europe and the US can be gauged by observing the downward trend in their purchasing managers’ indices (Figure 2). These , which cover the manufacturing and service sectors, are constructed such that readings above 50 indicate expansion while those below point to economic contraction. In both the US and the Euro Zone, the indices have been declining for the last year and a half, implying slower growth. Moreover, they fell below 50 in July, suggesting output in these economies is contracting.

Figure 2

Economic weakness in its trading partners means reduced demand for China’s exports.

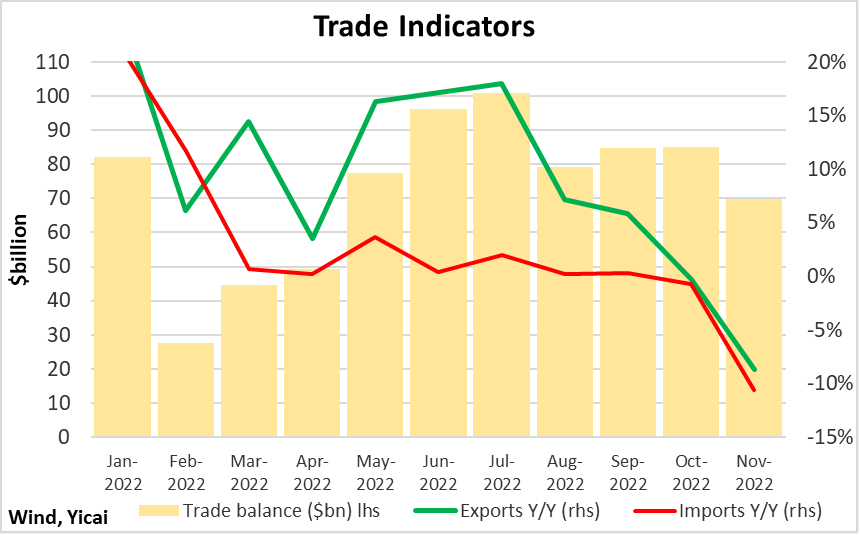

China’s export growth had been very rapid from early 2021 through July this year but it began to decelerate in August. It fell 9 percent year-over-year, in dollar terms, in November following no growth in October (Figure 3).

According to the NBS, November’s drop in exports was a contributing factor to the slowing in industrial value added. Nevertheless, with China’s imports declining by 11 percent, November’s trade balance remained relatively large.

Figure 3

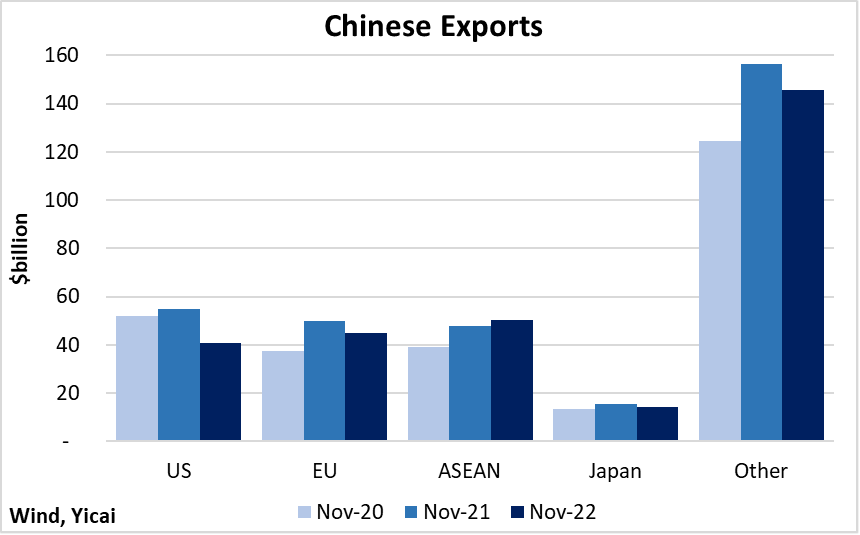

ASEAN is the only region in which China’s November exports remained higher than a year ago. Moreover, in aggregate, November’s exports were 11 percent higher than those two years ago. This means that some of the weakness we are seeing is simply the result of very strong growth last year. The US is the only region in which November’s exports fell below those of the same month in 2020 (Figure 4).

Figure 4

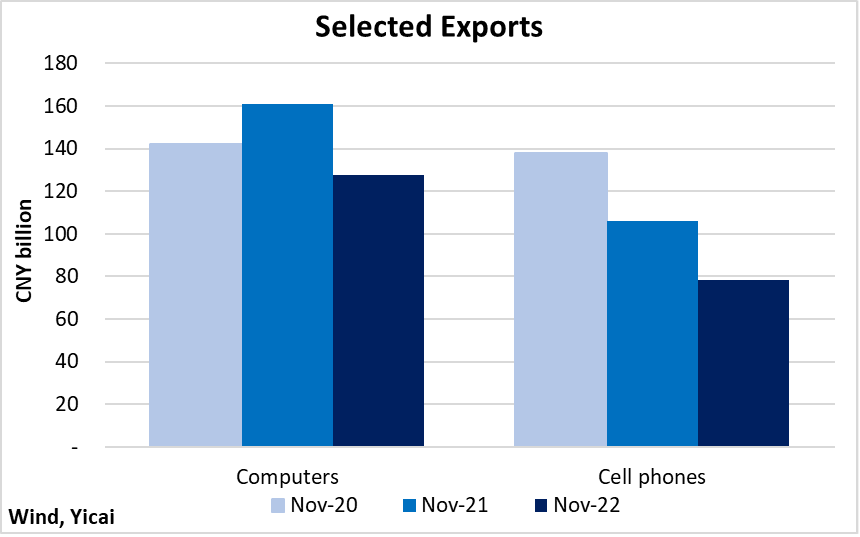

Tighter monetary policy in China’s trading partners is not the only factor that has dampened export sales. The demand for computers and cell phones, which was very strong in previous years, has cooled as this cycle of upgrades has been completed. As a result, China’s exports of these products have fallen (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Turning to China’s domestic market, November’s retail sales fell by 6 percent year-over-year. Sales of goods (-5 percent) and catering revenue (-8 percent) suffered from increased consumer caution in the face of rising infections and lockdowns in a number of cities.

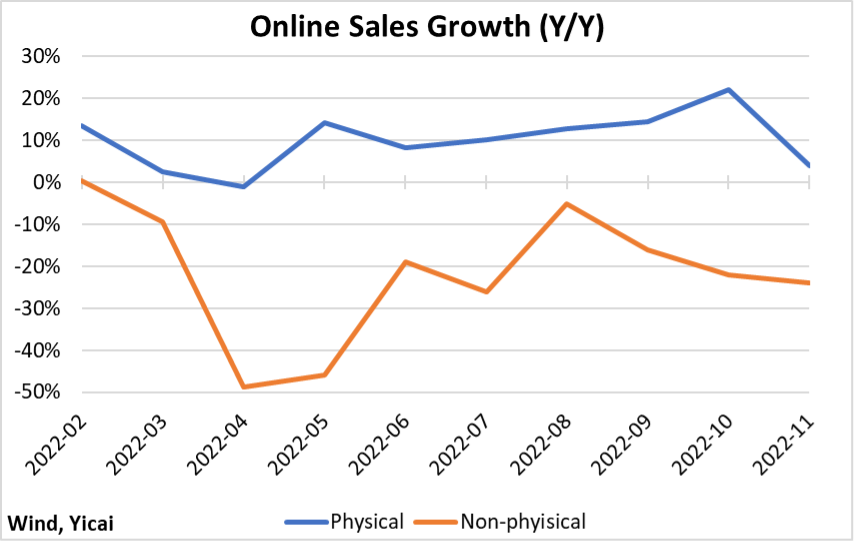

The data on online sales show just how cautious consumers became in November.

Sales of non-physical goods have been weak all year long as close personal contact increases the risk of infection and of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Online sales of physical goods had remained robust since shopping on your computer is safer than going to the store. However, in November, the growth of online sales of physical goods slowed significantly (Figure 6). This suggests an increase in precautionary saving.

Figure 6

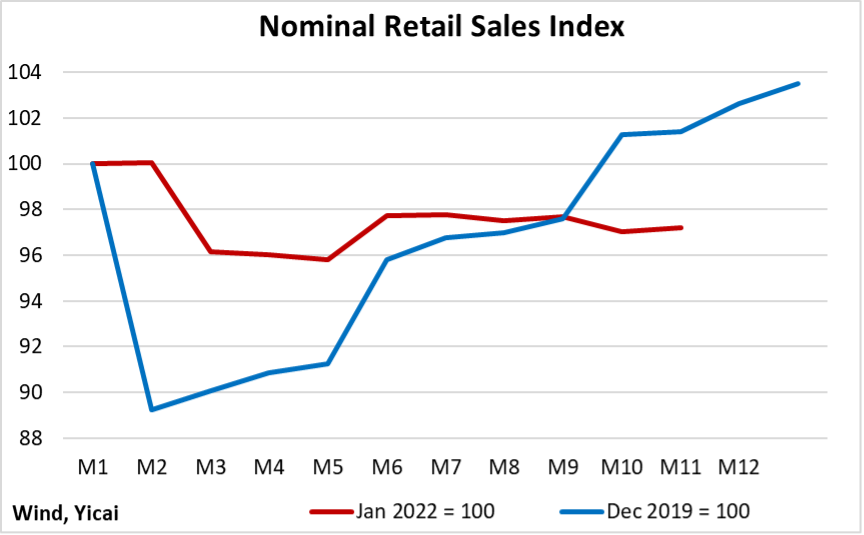

Indeed, this wave of Covid seems to be having a bigger effect on consumer confidence than the one in 2020.

The first wave was concentrated in Hubei Province and it was brought under control quickly. As a result, retail sales fell sharply early on but after 10 months they reached a new high (Figure 7). This wave is harder to contain and it affects more Chinese regions. The initial decline in retail sales was less severe. However, the retail sales series has yet to show a positive trend.

Figure 7

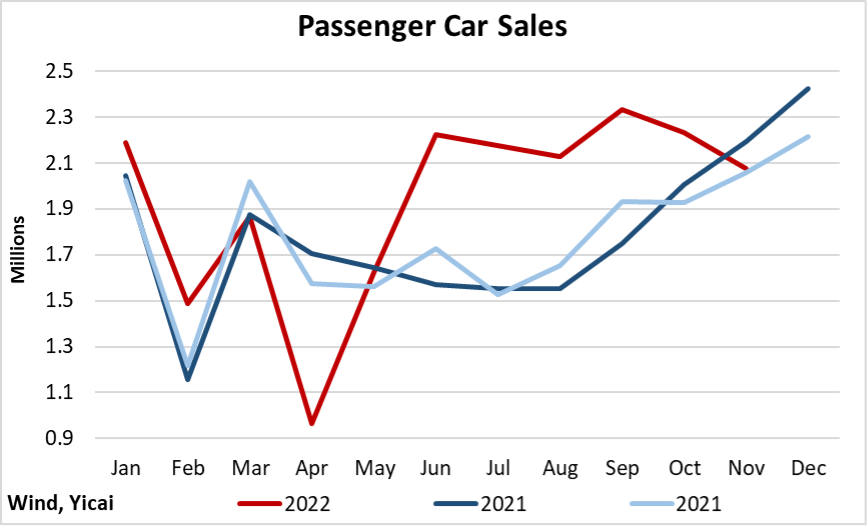

Even though consumers have been reluctant to spend this year, the car market had been a bright spot. In the year-to-October, the volume of passenger car sales was up 14 percent. Car sales in November fell below year ago levels, although it is not clear if this represents a new trend or simply a pause (Figure 8).

In November, car buyers continued to purchase new energy vehicles. Indeed, these green cars accounted for close to 40 percent of November’s sales, up from 23 percent a year ago.

Figure 8

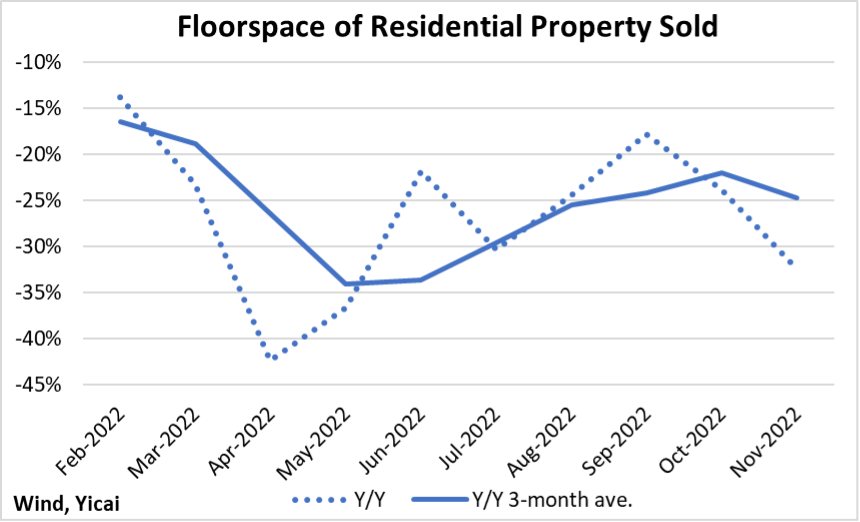

There had been signs that the falling demand for new homes was bottoming out after reaching a low in April (Figure 9). But the market weakened again in October and November, as the recent spike in infections reduced people’s willingness to purchase residential real estate.

Figure 9

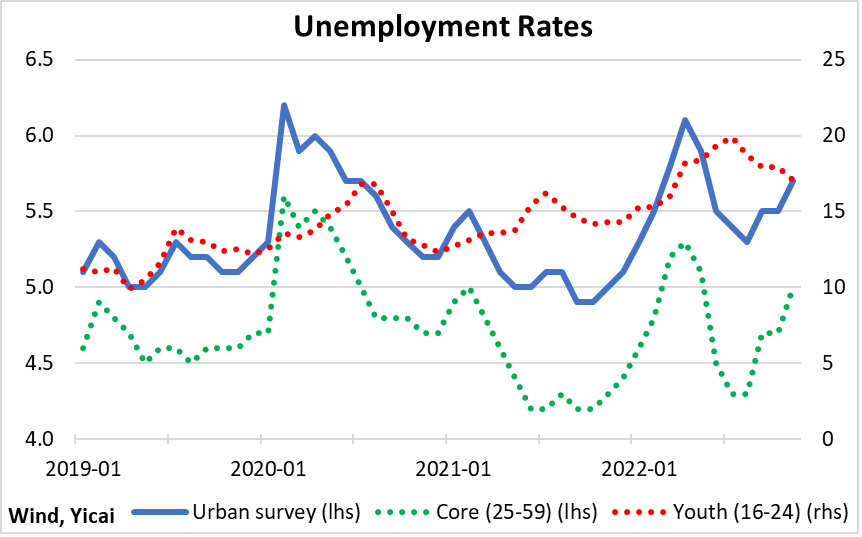

Weakness at home and abroad is translating into reduced demand for labour and rising unemployment (Figure 10).

After reaching a recent peak of just over 6 percent in April, the headline unemployment rate fell to 5.3 percent in August, as a better market for core workers – those aged 25-59 – more than offset a rise in youth unemployment.

However, since August, this process has reversed. The unemployment rate for core workers has trended up and is now higher than pre-pandemic levels even as the youth unemployment rate has fallen.

Figure 10

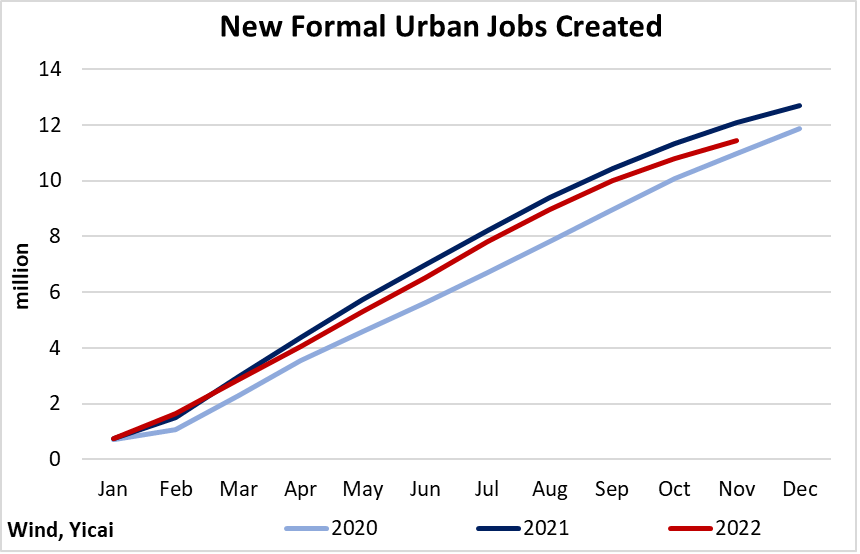

In the year-to-November, 11.5 million new jobs were created in the formal urban labour market. Thus, the government has met its target of 11 million for the year as a whole. Still, employment creation, so far this year, is 11 percent lower than last year and the pace of job growth appears to have stalled somewhat in recent months (Figure 11).

Figure 11

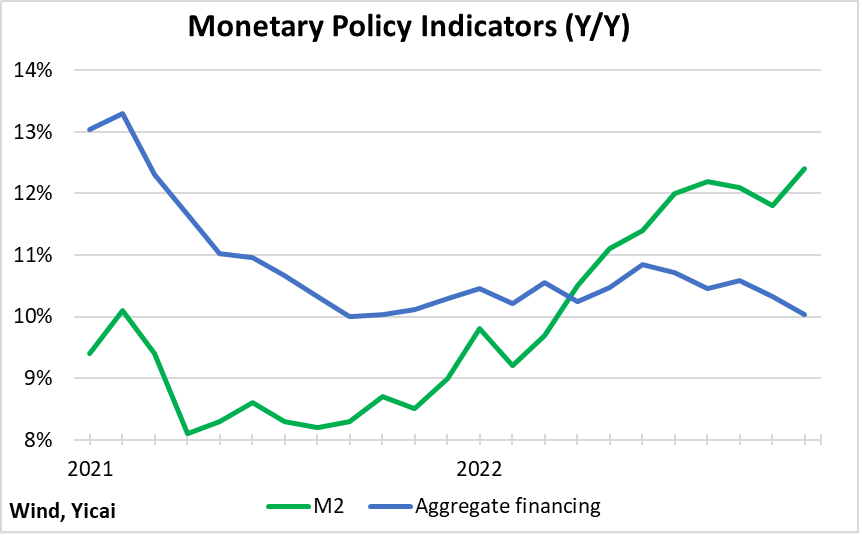

The authorities have responded to the slowing economy by loosening monetary policy. As a result, the growth of M2 accelerated to 12.4 percent in November from 8.5 percent a year earlier.

It is telling that the demand for credit has not responded to looser monetary conditions. The growth of aggregate credit was 10 percent in November, the same rate as a year ago (Figure 12).

With investor confidence low, monetary easing results in a build up of deposits but not the financing of new projects. This “pushing on a string” suggests that government spending – including additional investment by state-owned companies – may be more effective in supporting the economy. Infrastructure investment, which is up 9 percent this year and has accelerated for seven consecutive months since May, is a positive sign.

Figure 12

Preliminary indications are that things could get worse before they get better.

The mobility gap for the first two weeks of December widened from November’s average. Moreover, there is a lot of uncertainty about how people will react to the relaxation of public health policy which offers greater freedom of movement but increases the risk of infection.

In my neighbourhood, there is a renewed push to vaccinate older residents. This is a good sign because by rolling up our sleeves and taking the shots, we both improve our immunity and support the economy.